Ágnes Pálfi – Zsolt Szász

Ethnic and / or Professional Identity?

Flash Report on MITEM 2019

Zsolt Szász: In 2014, as preparation for the first MITEM, the March issue of Szcenárium had two quotations by Eugenio Barba chosen as a motto for the professional programme titled Identity – Sacrality – Theatricality, both taken from the 1993 book titled Paper Canoe[1]. The same issue also included an interview with the director made in 1985, that is prior to the regime change, on the occasion of Odin Theatre’s first appearance before the Hungarian audience, by The Gospel according to Oxyrhincus at Szkéné Theatre, in the autumn.[2] Now, having seen the MITEM 2019 productions, we think it is worth taking stock of these dates and the changing of times.

Ágnes Pálfi: Already back in 2014, we wanted to ask Eugenio Barba (who could not come to our professional programme at the time) whether he was still maintaining his view that one’s professional identity would override their ethnic and personal identity since the former may be shaped by one as a “rational being”. We would also have liked to challenge him if there was indeed no “genius loci” in culture. Related to this, we could have thematized Hungarian philosopher Béla Hamvas’s treatise[3] on the distinct spirits and mentality of the five geniuses characterizing and embodying the respective Hungarian regions, which together add up to be what is Hungarian.

Zsolt Szász: Perhaps Barba would not respond to our question any different today. But if I think back to earlier MITEMs, productions with a manifestation of the genius loci were always memorable. What did surprise me of the trilogy by Barba’s international troupe at this year’s MITEM, however, was the middle production, Great Cities Under the Moon, which made me understand what to them, one by one and as a group, that particular artistic identity, held in the highest esteem, means. In this performance-like production, they are sitting in a line, directly facing the audience, so that they are not protected by their roles and are exposed to the penetrating gaze of the viewers. They only express themselves for an etude, as if handing over their business cards, and back they are on their seats again. It must be no coincidence that the only instance from Brecht’s Mother Courage amounting to a scene is the evocation of the role of the voiceless girl (played by Iben Nagel Rasmussen), who is trying to warn the city dwellers, fast asleep, of the enemy approaching. This absurd situation raises the question whether the so-called “innocent” artist may in fact be held responsible for what is happening outside the world of theatre. There seems to be no straightforward answer to this question. However, one thing is clear: the diverging elements of this performance are brought together by the telegraphic “testament” of the martyred Canadian peacekeeper, who, having gone through the wars in Bosnia, Afghanistan and Iraq, is supposed to document and represent the helplessness of the man of today. This monologue-like text montage reminds me of the scene when in the play Fabulous Men with Wings, directed by Attila Vidnyánszky, the actors relate in the first person singular the story of the death of the rocket constructors and disregarded cosmonauts who survived the Gulag, in order to demonstrate the here and now stage presence of the dead they have summoned.

ÁP: Narrative techniques of this kind are getting more and more common nowadays. MITEM this year had them in several performances and with different functions. In Saigon and The Alien, this type of storytelling gives an epic frame and some kind of perspective to the scene which is taking place in the present. In the case of Saigon for instance, at first it is as if we were watching a home cinema, discovering ourselves and our friends from decades ago, “Oh, that’s me over there, d’you recognise me?” And then it becomes more like watching a telenovel, with subtitles indicating the number of the episode as well as the time and location, whether it is Paris or Saigon – which, after all, makes no difference, since, all along, we are staying in the very same Vietnamese canteen, equipped with naturally specific objects. Moreover, the restaurant’s owners are amateur actors who have been doing the same in real life. The Alien, like Saigon, is set in the same stage space all through the play: we see a wooden house, which turns out to be a replica of the one where the protagonist once lived in Tartary. So, although a Canadian resident for decades, he is surrounded by the same environment as if he was at home. That is why he does not bring himself to return to his homeland. If you come to think of it, both stories are actual descriptions of statelessness in which the genius loci loses sense indeed[4], but these heroes are – why? why not? – unable to take root at the new place, either. And this in-between situation does not seem to favour the plot taking a dramatic character, even if there are inexpressible historical cataclysms behind these private human life stories.

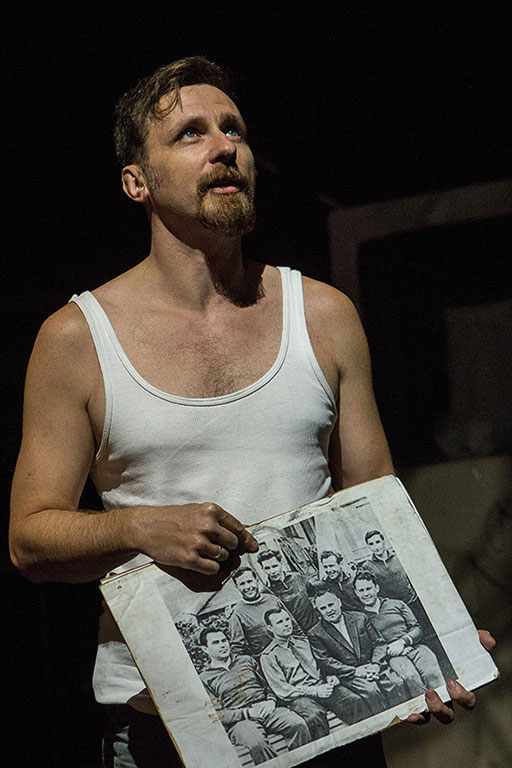

(photo: Zsolt Eöri Szabó)

ZsSz: I also felt this in-between state during both productions. That is one reason why it was interesting when the actors at the talkback session following Saigon spoke positively about their dual identity, which of course may be attributed to the success of the performance, too. Anyway, France, where this production came from, has a several-hundred-year-old tradition of multiculturalism. Yet, even there, mixed language performances are – or at least that is what I presume – still a curiosity, and typical of experimental theatres mainly. The increasingly popular physical theatres, though, have ab ovo superseded verbality. Presented by João Garcia Miguel & Teatro Ibérico from Lisboa, Garcia Lorca’s play, The House of Bernarda Alba, which is known to bring into view the dramatic character of Spanish mentality, has been special in this respect, too. Interestingly, this Portuguese- and English-language production, in which the title character and her housekeeper are both played by male actors and there are only two in the cast for the sisters, retains its original ethnic nature. Moreover, and to our surprise, this nature is enhanced when the director has the English actor introduce the story by an ancient Japanese creation myth, that is an epic prologue, which then turns out but to serve the interpretation of the drama.

ÁP: Of course, the basis for success here is an excellent drama, which can even withstand that the characters’ innermost passions be conveyed in a completely abstract space by physical theatre tools. The Idiot is also based on a masterpiece which remains intact from even such a cut-back interpretation as for example director Andrzej Wajda’s two-character play in Krakow, with Myshkin and Rogozhin over the body of Nastasya Filippovna. Nonetheless, Jókai Theatre in Komarno, Slovakia (d: Huba Martin), essentially put the entire, even if somewhat slimmed down, plot on stage, ignoring Dostoevsky’s recommendation that in dramatizing a novel it is actually worth creating a new piece, either by carrying through the initial idea or highlighting a particular episode[5]. In this case, however, I think the director was right when, in knowledge of the capabilities of the company and that it had two accomplished actors suitable for the role of Myshkin and Rogozhin, he set out to create such a production as is able to introduce the spectator who is just getting acquainted with Dostoevsky to the world of the novel and the theatre at the same time.

(photo: Révész Rebeka, source: kulter.hu)

ZsSz: It is not only the problem of dramatic quality which arises in the case of narrative texts – novels and short stories. I think it is much more a question of what kind of theatricality it is which can breathe life into these texts, and how these figures can make it from page to stage. An example of this dilemma at MITEM 2019 was Sons of a Bitch directed by Eimuntas Nekrošius, who passed away last year. This world-famous Lithuanian director is notable exactly for creating a whole new stage language in his home country through the concrete, and at once symbolic use of ancient elements and objects. The selected postmodern novel, in the making for 20 years before the regime change, is not yet available in Hungarian. Still, the focus of the production – so abundant in texts – emerges clearly: it is the self-image of the Lithuanian people, the historical background of its identity as well as the pagan and Christian roots of its faith. Nevertheless, no matter how much we are accustomed to the form of narration represented here by Karvelis, the ringer (Darius Meškauskas), who holds together the threads of the story and their symbolic imagery, this magic trick was hard for the Hungarian viewer to decode. The director of the production Morituri te salutant by Ivan Franko National Academic Drama Theatre, Kiev, Ukraine, also faced a tough nut to crack when he staged the best-known short stories of the Ukrainian national author, Vasyl Stefanyk. Ditro Bogomazov did not even make an attempt to create characters individualised in the dramatic sense of the fancifully poverty-stricken figures in the collection of short stories. He preferred to use the tools of stage animation, showcasing its entire arsenal. The actors moving about in the abstracted space, just like on the puppet stage, sometimes set into motion only one part of their body, sometimes join three persons to form one, sometimes act as singers or instrumental musicians to represent the collective Self, which or who emerges in the spectator’s consciousness by the end of the performance as, behold, here is the Ukrainian man, here is the national genius who comes out on top in the most impossible situations in life! The key to his success lies apparently in that every move he makes springs from the playfulness of homo ludens. As a viewer, I had the impression that professional and ethnic identity mutually reinforce each other and fully overlap in this production.

ÁP: However, Eirik Stubø’s production is expressly about professional identity and its crisis. Throughout the performance, we are looking at the three protagonists of Tarkovsky’s film, The Sacrifice, in an in-between situation, during a forced time out in filming, when the question of the final motives for making film or theatre inadvertently arises. In other words, we are witnessing a classic “theatre in the theatre”, with that at stake whether these Swedish actors, who are now playing themselves so to say, will find common ground with the Russian director whose mindset they are tightly bound to via the great Swedish director, Ingmar Bergman. Will they be able to escape from the captivity of the double mirror in which they now see caricatures of themselves and each other? Will they not fall back into the over-reflected and alienated state of existence, which was, in fact, not the invention of postmodern or post-dramatic theatre, but the spirit of the 1960s? This inner drama is authentically brought to life on stage by middle-aged actors who grew up with Bergman’s films and therefore personally carry the “Swedish code”, thanks to which they are able to pose, beyond continuous self-reflection, the ultimate existential questions to one another and themselves of faith, love, death or loyalty to one’s profession.

ZsSz: Actor’s life as a theme is the same, but the approach is characteristically different in the production by Divadlo Na Zabradli theatre, Hamlets (d: Jan Mikulašek), representing a comic variety, traceable back to the Middle Ages, of the Czech theatre tradition. At first glance, this play, with the women’s dressing room in the theatre as a location, may seem like a revueish garland of cabaret jokes, gags and sketches. The jokes follow each other in such quick succession and with such abrupt changes in perspective that what we see is both ridiculous and astonishing or embarrassing. The spectator is wondering more and more what the aim of this piece is, which reveals with unabashed sincerity the clichés of the acting profession, the superficialities in playing and the nerve-wrecking daily routine. It may remind us of Stanislavski’s statement when he compared the actor to a gold digger whose work is ninety-nine percent stonebraking, and only one percent is the award for which he has taken up acting with the “stubbornness of a person in love”. The gradually darkening overall image shows the full physical, psychic and intellectual exposure of the victim of the profession. His escape attempt is futile because he comes to realise that he cannot accept the loneliness of mass man in a consumer society, so to exist in this ’colourful hell’ is still a better choice for him. So this conclusion is not lacking in a socially critical attitude, either: here, theatre as a cruel life substitute confronts the outside world, the “unbearable ease” of being for European man.

ÁP: Earlier MITEMs also saw plenty of productions focussing specifically on the cultural heritage and / or identity crisis of ethnic communities. To mention but a few of the memorable examples: the mythical hero of the Hungarian people was memorably evoked by Isten ostora (Flagellum Dei) (d: Attila Vidnyánszy, 2015) about Attila, king of the Huns, taking a secessionist piece, Miklós Bánffy’s drama on Attila from the early twentieth century as a starting point. The shared “ethnic code” of the Eurasian Turks was marked in the performance by Éva Kanalas’s archaic recitative, which she composed of Hungarian cradle songs as well as Tuvan shamanic songs. Another piece worth remembering is the Yakut Titus Andronicus (d: Sergei Potapov) featuring at MITEM 2016, which was able to bring to the surface the most archaic layer of Shakespeare’s drama through relating the story in the language of heroic epics which bears the Yakut ethnogenesis and archaic tribal culture, incorporating the Olonko tradition.[6]

ZsSz: Many did not consider the Jindo island, South Korea, Ssitgimgut shamanic ritual, celebrated in the same year by Korean traditionalists, as a theatrical production. This funeral ceremony would have deserved more attention though not only on account of its exotic nature, but also because drama and theatre are rooted in the rites of the cult of the dead in all cultures around the world. With respect to its stage realisation, The Legend of Korkut (d: Jonas Vaitkus), presented by the Kazakhs at MITEM this year, also narrates in a ritualized form the story of the way in which the mythical ancestor of the Kazakhs died. In connection with the film extract used in the production, the symbolic reading also offers itself that the author of the play, Iran-Gayip, would in fact be identical with this culture hero, squabbling with the creator of the world, Tengri.

ÁP: On a personal encounter with the author, we could see that as far as the role and dedication of the artist is concerned, he shares views with Attila József, who derives himself as well as his poetic genius from his ancestors: “They speak to me, for not I am they, robust / Despite whatever weakness made me frail, / And I think back that I am more than most: / Each ancestor am I, to the first cell.” (A Dunánál – By the Danube, translated by Vernon Watkins).[7] As for the title character of the play, Dulida Akmolda reminds me not of the culture hero, but more of Jesus, the son of god, who [Dulida Akmolda], according to the lineage in the story, will be followed by his son named Kazak, the originator of the name of the nation.

ZsSz: But once we are looking for the “ethnic code” in the mode of acting, we find that it only becomes really tangible at the dramatic climax of the story. It happens in the series of scenes directly preceding Korkut’s life sacrifice, the conflict situation of which is akin to the “love test” story line in the treasure chest of Hungarian balladry or as can be found in ancient Greek drama, too (see Euripides’ Alcestis). From this series of scenes counterpointing the tragic denouement, created in the spirit of parodia sacra, one could infer the mode of acting which Kazakh theatre may continue to cultivate as its own ethnic tradition even today. However, the performance as a whole, thanks certainly to the Lithuanian director and composer, was characterised more by the toolbox of contemporary world theatre and multimediality, as well as the choreographed movement culture which reminded me of the former revue productions by the Soviet-Russian nationalities. Many of us missed the live sound of the Kazakhs’ national instrument, the kobyz, which is otherwise playing a key role in this mythical creation story.

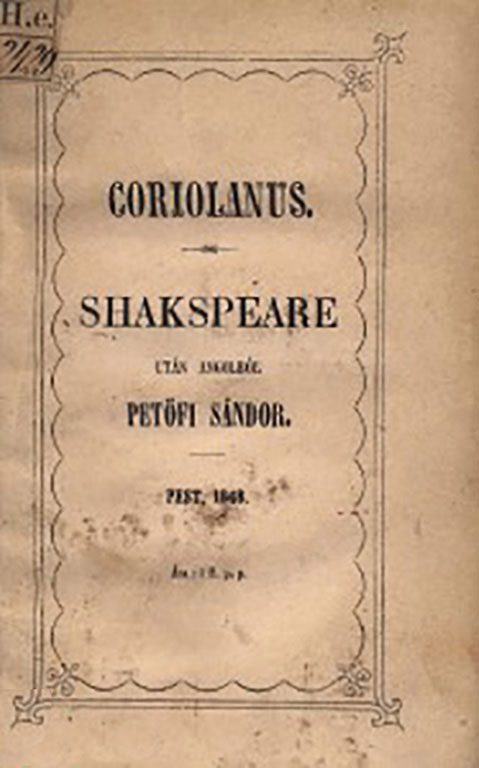

ÁP: Ukraine is a young nation-state, like Kazakhstan. No three decades have yet passed since it seceded from the Soviet Union, and it is going through the most intense stage of its search for identity today. By a strange quirk of fate, the day after the premiere of Coriolanus at Ivan Franko National Academic Drama Theatre, the Ukrainian parliament adopted a language law violating the fundamental human rights of the Hungarian minority there. So it was a bold decision by both national theatres to opt for this particular Shakespeare play for MITEM 2019, which piece, as the director, Dmitro Bogomazov said at the talkback session, can be interpreted as a parable of today’s Ukrainian political relations. (Involving the failure of democracy and dictatorship at the same time, the play was banned by no accident in Stalin’s Soviet Union.) However, the success of the production is not attributable to this obvious political topicality, but to the high-calibre director, who approached this ancient story from the elevated point of view in the original work. It is as if Shakespeare had created a counter-piece to Macbeth by this play: while Macbeth as a victorious warlord seizes also spiritual power via regicide, the tragedy of Coriolanus stems from his unwillingness to use the power offered to him. It is, on the one hand, because he cannot, and does not want to comply with the rules of the game disguised as democratic, and, on the other hand, because he realizes that his military virtues and strength of character do not yet predestine him to become also the spiritual leader of the community. It is, in fact, this insoluble contradiction that leads to the voluntary sacrifice of his life, which, in the light of the protagonist’s (Dmitro Ribalevsky) remark at the talkback session (ie. there are very many Coriolanuses in Ukraine today), makes one think indeed.

ZsSz: It is no accident that the symbolic object in the performance is the Roman statue from the hand of which Marcius captures his all-powerful sword. Equally indicative is the fact that in Act Two the very same statue is present already deprived of its divine rank, as a decapitated torso only. This pathos-filled production reminded me to ask why Sándor Petőfi encouraged his poet friends, Vörösmarty and Arany, on the day after the outbreak of the 1848 Revolution, to translate Shakespeare’s works, and why his choice fell exactly on Coriolanus. I venture to say that this was because he, as a poet-king, looked upon military virtues as some human ability on a par with spirituality, an ambition to rescue the nation. This piece very rarely plays in Hungary, that is why it would be exciting if young actors at the National Theatre in Budapest took up staging Petőfi’s Coriolanus in their own interpretation for the 2023 bicentenary. Then it would be possible to tell whether these great driving forces behind national romanticism still existed for them.

ÁP: It also took some courage for the National Theatre to invite the Berliner Ensamble’s company for the second time. In fact, it had been uncertain until the last minute whether they would accept, because we, the inviters, had failed to meet their precondition of holding a roundtable discussion with the theme of democracy deficit in Hungary prior to their performance. In the end, there was only a proclamation presented by them at the MITEM press conference to express their faith in the liberal concept of democracy. Compared to this, their choice, A Streetcar Named Desire by Tennessee Williams, was free from any topical political allusions. I remember that a member of the most likable young company remarked at the talkback session that they themselves had asked when rehearsals began whether what message could be conveyed by this piece today. They added that they were also surprised by the success of the performance at home and abroad.

ZsSz: It needs to be acknowledged that Michael Thalheimer’s rendition is a thoroughly professional one, and that the German actors did their very best, like in last year’s Caucasian Chalk Circle and The Tin Drum. However, I found the two former productions more exciting than this year’s one on account of the elemental power in the determination to artistically process the German people’s 20th century traumas. At the same time, the stage space of A Streetcar Named Desire will, I think, remain memorable to all of us: a space triangle cut out of a huge cube, with an inward opening floor tilted at an angle of 30 degrees, where mere coming and going amounts to a breakneck stunt for the actors. This designer-director’s concept makes it clear from the outset that everything in this production will be about comedown. What I as a spectator perceive elementally is that I am beginning to worry about the actors’ safety, therefore I am compelled to identify with the physical efforts they are making in order to stay alive. This pre-calculated mechanism stays in effect throughout the performance, which I, a man of feeling, cannot get rid of.

ÁP: This is precisely why we have the overall image emerging that while the characters played by the actors are heroically tackling this almost impossible task, the material challenges of life deprive them of their energy to conquer social conventions as moral beings. To overcome those reflexes which stifle their spiritual aspirations, and do not let them find a solution to their – in fact – not at all hopeless life situation. That is why Blanche and Mitch’s planned marriage fails, as a result of which Blanche is no longer able to stay, even in the physical sense, on her feet, thenceforth crawling up and down the slope in her wedding dress. Perhaps it is this directorial reading of the play, having premiered in 1947, that captivates the European spectator who, accordingly, experiences the same dichotomy in their daily lives.

ZsSz: Still, if you take only Blanche’s spiritual trauma itself, it could easily be remedied by an ordinary psychologist in America today. Since no matter how shocking the autobiographical background to the play is, the story itself now seems more melodramatic than tragic. To puzzle out why, in contrast, interest has never been lost in Chekhov’s dramas (played in a nostalgic and melodramatic tone in Hungary in the 1960s, at the time Tennessee Williams’s piece was discovered) goes beyond the scope of this discussion. Yet it is worth asking the question itself, because this year’s MITEM featured as many as three of Chekhov dramas. This also indicates what we have seen in Hungary over the past few years, too, that playing Chekhov is enjoying a worldwide renaissance again. However, these recent productions do not resemble the interpretations of the ’70s and’ 80s, which were characterized, in both the East and the West, by a kind of cool aestheticization, a rococo-like stylization, as if time around Chekhov’s figures had frozen.

ÁP: The intimate familiarity and full-bloodedness, together with the “museum-like” stage space of Ivanov by the Serbian National Theatre, directed by Tanja Mandiċ Rigonat, reminds me of the efforts these days to try and fill empty exhibition halls with life by all sorts of performances so that visitors feel at home among high-culture works of art. Contrary to the director’s statement[8], however, I think this performance is not so much the live museum of Ivanov’s (Nikola Ristanovski) as of the other characters’ in the play. For the title character of the drama, with his so-called impossible questions and obsessive search for the meaning of existence, would by no means fit into a group picture of the typical figures of the play to be hung on a museum wall. These characteristic Chekhov figures who surround the protagonist seem to have an everlasting life, though. The vividness of the explicitly realistic, and occasionally naturalistic mode of acting, as well as the proximity of the playing area to the viewer, suggest that their unbridled gestures, hedonistic mentality and insane illusions are still to be encountered anytime, anywhere. This concreteness is counterpointed by the fourth element in the playing area: the still tableau, or still life of the band on the podium placed behind the empty picture frame. It is this symbolic medium of art where the dead wife (Nada Šargin), donning her wedding dress, will also enter. This directorial solution not only emphasizes her loneliness, but also expresses that her detachment is different from Ivanov’s, who commits suicide as an escape: Anna Petrovna transitions from life into the museum space of remembrance as the statue of an unrealized artist.

ZsSz: Nonetheless, at the end of the other Chekhov piece this year, Tuminas’s Uncle Vanya, there is indeed a group photo taken, which stiffens the characters for a moment and freezes them into a tableau. Yet this photo machine is not a camera, but a laterna magica, the ancestor of the projector. In a much earlier scene, Astrov (whose name speaks for itself referring to the world of stars) presents the true story of his life condensed into three images to Sonya, who is staring into the contraption. The first picture shows a wide open place, the second one a garden cultivated by himself, and the third one a misty sunset. Another key scene of seeing and making seen is when, in the course of a conversation, Uncle Vanya, out of the blue, but in the most natural way in the world, lifts a glass strip from the carpenter’s bench, chars it over a candle, and gazes at the sun through it; then he hands it over to Sonya, who will also get immersed in the sight. We are looking at them and we can imagine what they see. The only disturbing factor is that from the background, in the middle, there is a stone lion staring at us throughout the whole performance. We do not know what this petrified gaze can see of the performance and of us. One thing is certain: the characters in the play are moving in the crossfire of the spectators’ and this mythical being’s eyes. If we want to decode Tuminas’ directorial thought and the mechanism of action in the production, I think it is worthwhile to take this complex vision as a starting point.

ÁP: In an interview[9] after the Moscow premiere of the piece, Tuminas regrets that theatre practitioners today tend to forget about the “third eye”. He says, putting it straightforwardly, that acting would need to be taking place in front of the cosmic gaze of the unknown (divine) being above us in order to establish a dialogue between the actors on stage and the spectators. I think this enigmatic lion figure makes this particular third eye present here. And through the solar symbolism, it also represents the higher, cosmic level of existence which the characters in this piece – with the pale-glimmer lampshade floating over them in the background to symbolize the setting sun– can only look at through the sooty glass (by the way, this lamp may also refer to the Sun’s loss of vitality, its eclipse). Let me add that 19th-century Russian literature boasts fallen “sun heroes” as well; Dostoevsky’s Raskolnikov and Stavrogin exhibit this mythical format[10].

Zsolt Szász: It is a commonplace that Chekhov’s dramas have no real dialogues, no interchange, the characters keep talking past one another, and they are in the state of continuous monologue. Many people still think that this is what makes these plays epic, and that the director should first and foremost have the actors say these monologues so-called authentically. Others misunderstand, in my view, why Chekhov calls his plays comedies when most of his stories end in death, or at least ’Chekhov’s gun’ is always there to go off at the end of the play. The radical novelty of Tuminas’s interpretation of Uncle Vanya, like Purcarete’s The Cherry Orchard’s[11], lies in approaching the plot, as well as the texts recorded in the drama, from theatricality. Both directors cut and break these large bodies of texts to a great extent, and have the characters say their own lines in a way that they are simultaneously acting out what they verily think and want to do in the meantime. The most conspicuous example of it in Uncle Vanya is when the title character (Sergei Makovetsky) is beginning to undress while saying his lines, then jumps onto the couch turned with its back to the audience, and only his legs protrude, which looks as if he was fornicating with the professor’s wife, Yelena Andreyevna (Anna Dubrovskaya). The scene is more than comic, evoking the burlesque style of silent films, just like the unsuccessful attempt later to shoot the professor. This extremely theatrical approach overrides the “solemn anthem of hope”[12] in Uncle Vanya and Sonya’s closing scene, and underlines the paradox Tuminas has referred to in the above-mentioned conversation, alluding to Pushkin: “… Comedy is not intended to amuse viewers, or to evoke a chuckle, it is not a call to laugh, because (…) more often than a tragedy, it has a tragic end.” [13]

ÁP: All this reminds me of an astonishing experience back in the mid-seventies of the last century. As a visiting graduate with a Russian studies major, I made friends at the Moscow hostel called ’house for aspirants’ with PhD students, one of whom always related her own life drama during the ritual evening “tea ceremony”. And I noticed that these feminine confessions of a melodramatic tinge, each and all of them, seemed to have been cut out of Chekhov monologues and reproduced in a customized way. I believe that this perpetual propensity in human nature for self-pity greatly contributes to the enduring popularity of Chekhov dramas. As far as the comic aspect of this phenomenon is concerned, these Chekhov monologues are, in fact, parodies of romantic prose popular in the era, including even the solemn lines of certain romantic-spirited Dostoevsky heroes. Let me remark that parody as such is a most central concept in Russian literary theory; it is enough to refer to the work of Bahtin alone.

ZsSz: As a theatre practitioner, of all his writings, I have made the most of Bahtin’s study on “folk laughter”. Having seen several of Purcarete’s directions, if I had to define the genre of The Cherry Orchard in one word, I would say that it was also a death dance, like his Gulliver and Faust. This medieval genre is never concerned with lonely individuals’ sadness rooted in the fact of death, but with the collective experience that life does not let us become immersed in the dread of the awareness of the finality of human existence. But again, this presupposes that the command of “memento mori” should be integrated into our everyday lives.

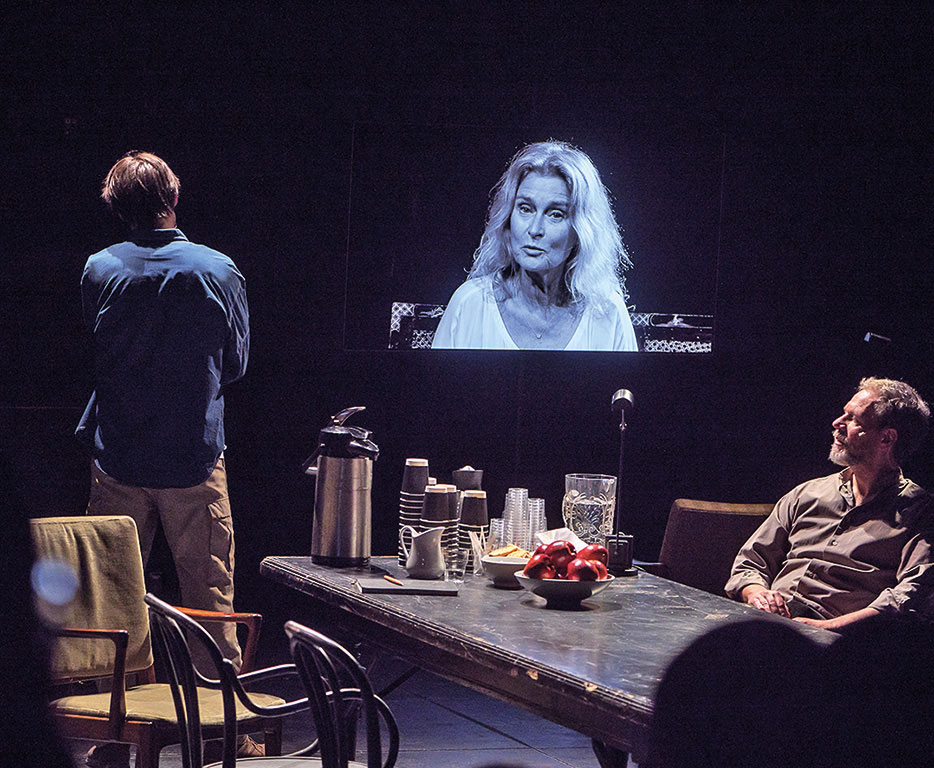

at the National Theatre, Budapest (photo: Zsolt Eöri Szabó)

ÁP: It is no coincidence that archaic evening prayers also include this formula: “Into my bed I lie down sleeping, my body’s coffin every evening” (where the Hungarian original boasts a poetic surplus raising awareness to the relationship between the words for ’evening’ and ’body’). But nowadays, people are forcefully argued out of this “outdated” approach both by mass communication as well as postmodern philosophers, who think that our death is an event beyond our control. By that it is also suggested that there is no point in taking the ethical imperative of “memento mori” seriously, so, to put it bluntly, we have no chance of daily resurrection, either.[14]

ZsSz: The Cherry Orchard is known to be the death-stricken Chekhov’s last drama, or his farewell symphony, if you like (it premiered at the Moscow Art Theatre just six months before his death). The personal involvement is strongly emphasized in the motif of chopping down cherry trees in blossom. The drastic nature of this, the aggressive form of the deliberate destruction of life, is brought to our attention by the sound of the chainsaw and the immediate vacuuming up of the sawdust. But an even stronger emphasis is placed, in the symbolic handling of the story, on the fact that the actors are playing on a plastic surface, illuminated from above, which, by spreading it, reflects light multiplicatively. This has the same effect as the downstage illumination by candles and mirrors of former Baroque stages, which turned the characters into larval-faced ghosts. This scenic solution may give today’s spectator the feeling that those who step up here are all already dead. The real world is to be seen dimly behind a translucent plastic foil stretched across the full width of the back stage, where passage is possible only through a narrow doorway. Through which, from beyond, only Tramp-Firs, donating thirty kopeks, that is Death alone can enter the acting area. It is worth mentioning here what Purcarete’s instructions to Zsolt Trill, playing the old servant Firs, were: “You are 500 years old in this role”.

d: Silviu Purcărete, the final scene (photo: Zsolt Eöri Szabó)

ÁP: By this the director has also drawn attention to the fact that time dimensions are beyond the realm of everyday reality on this stage. In the light of the closing image, we may even risk that this stage is already the gateway to apocalypse, and that is why the characters in the play keep putting off crossing this threshold. Whereas all of them have, in fact, stepped over the boundaries of social conventions and are able to do things intolerated by etiquette not only at the time when the piece was written, in 1904, but even today. An outstanding example of this is the scene of Ranyevskaya (Dorottya Udvaros) sitting in the lap of the student living with the landowner family and obsessed with anarchist ideas (Roland Bordás). Watching the play of their extended arms, it is impossible to tell who is having the upper hand in this battle of sexes and generations. This duet scene proves that, as with Tuminas, dialogue is not necessarily textual, and that the meta-language of gestures on stage may have an elemental effect on the viewer. No wonder that an acquaintance of mine showed special interest in the anarchist, played by Roland Bordás, saying even that had Chekhov foreseen the outbreak of the revolution in 1905, he would not have written this piece. Although this assumption may raise a smile, it certainly proves that Purcărete uses his usual radical means in this directing, too, and that he also reflects on specific current events. For example, Roland has told us that the director advised him to take the personality of a 1968 French activist, still active in European public life, as a model for building the character.[15]

ZsSz: MITEM has been characterized by multigenericity over the years, as well as by an ambition to have the opening ceremonies reach out to the general public. Remember the environmental productions of Teatro Potlach and Teatro Tascabile, or the 2018 Chekhov adaptation by the Ukrainian Voskresinnia Theatre in the bow. This year’s opening ceremony was different from the previous ones in the novelty of both genre and venue. Slava Polunin’s Snowshow at the Fővárosi Nagycirkusz (Capital Circus of Budapest) proved that circus art has been able to successfully renew itself over the past decades by taking possession of the tools of theatrical art. In return, we can see nowadays that the young generation of actors is becoming more and more receptive to circus art, is eager to learn the stunts of circus artists and acrobats as well as acquire the necessary physical skills. The Snowshow went down quite well with the public, children and adults alike; yet many in the profession asked: where does is have theatre in it? Presumably, they were overwhelmed by the bombastic theatricality of the show: the paper snowstorm to flood the audience, the clowns who kept insulting them, and finally the common passing around of the giant balloons. One may wonder if telling the tragicomedy of the little man in the language of gestures, as Polunin puts it, has failed to get across to them. Actually, this production aspired to represent the ancient form of theatre, the world of comedians, carnival figures and court fools, who, balancing on the border between life and death, obtained the wisdom that no king could ever be devoid of in times gone by.

Translated by Nóra Durkó

[1] “Our ethnic identity has been established by history. We cannot shape it. Personal identity is built by each of us on our own, but unwittingly. We call it ‘destiny’. The only profile on which we can consciously act as rational beings is the profile of our professional identity.” (p. 147) “There is no genius loci, genie of the place, either in theatre and culture. Everything travels, everything drifts away from its original context, and is transplanted. There are no traditions which are inseparably connected to a particular geographical location, language or profession.” (p. 146) https://books.google.hu/books?id=Cf6HAgAAQBAJ&pg=PA146&lpg=PA146&dq=barba+paper+canoe+genius+loci&source=bl&ots=Ucf31kTg1H&sig=ACfU3U2iO09lmmxjD8lO4AZb_0dflynAnw&hl=hu&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwj_rP3G7o_kAhUrposKHdlJAXEQ6AEwC3oECAkQAQ#v=onepage&q=barba%20paper%20canoe%20genius%20loci&f=false Cf. Hungarian edition: Eugenio Barba: Papírkenu. Bevezetés a színház antropológiájába (transl. Andó, Gabriella and Demcsák, Katalin; ed. Demcsák, Katalin; proofreader Regős, János), Kijárat Kiadó, Budapest, 2001, p. 184

[2] Eugenio Barba: “Szeretnék a színházammal mindenkit megérinteni” (“I’d Like to Touch Everyone Through My Theatre”) (Interview by János Regős), Szcenárium, March 2014, pp. 78–83

[3] Hamvas, Béla: Az öt géniusz. A bor filozófiája. (The Five Geniuses. The Philosophy of Wine) Életünk Könyvek, 1988

[4] See Gertrude Stein’s enigmatic remark of the United States: “there is no there” commented on by Northrop Frye in his Words with Power as follows: “…meaning, I suppose, that the beckoning call to the horizon, which had expanded the country from one ocean to the other in the nineteenth century, had now settled into a cultural uniformity in which every place was like every other place, and so equally <

[5] See Király, Gyula: Dosztojevszkij és az orosz próza (Dostoevsky and Russian Prose). Regénypoétikai tanulmányok. Akadémiai Kiadó, 1983

[6] See Pálfi, Ágnes – Szász, Zsolt: “Ez egy valóságos színházavató volt! Gyorsjelentés a harmadik MITEM-ről.” (“It Has Been a Real Inauguration of Theatre! A Flash Report on MITEM III”) Szcenárium, May 2016, pp. 48–49; Tömöry, Márta: “De ha a légynek apja, anyja van? TIIT: a jakut Titus Andronicus (“But how, if that fly had a father and mother?” TIIT: the Yakut Titus Andronicus), id., pp. 70–80

[7] 1976, Hundred Hungarian Poems, Albion Editions, Manchester https://www.magyarulbabelben.net/index.php?page=work&interfaceLang=en&literatureLang=hu&translationLang=all&auth_id=127&work_id=512&tran_id=1766&tr_id=0&tran_lang=en

[8] See interview with the director in the January 2019 issue of Szcenárium as attachment to Verebes, Ernő: “A lélek múzeuma” (“The Museum of the Soul”), pp. 41–43

[9] See “A gyöngéd erő színháza. Rimas Tuminas és Mayia Pramatarova beszélgetése” (“Theatre of Gentle Power. Rimas Tuminas and Mayia Pramatarova in Conversation”) (transl. and ed. Regéczi, Ildikó), Szcenárium, May 2019

[10] See Porfiry Petrovich talking to Raskolnikov in Crime and Punishment, encouraging him that after he has served his sentence, a bright future awaits him: “… What of it that perhaps no one will see you for so long? It’s not time, but yourself that will decide that. Be the sun and all will see you. The sun has before all to be the sun” pp. 643 https://www.planetebook.com/free-ebooks/crime-and-punishment.pdf

[11] Productions born at the National Theatre in Budapest and featured at MITEM 2019 are not reviewed here. Purcarete’s The Cherry Orchard is an exception to provide a fuller picture of the nature of Chekhov’s renaissance.

[12] cf. Szigethi, András: Az egzisztenciális idő Csehov drámájában. Ványa bácsi (’Existential Time in Chekhov’s Dramatic Poetics: Uncle Vanya’), Szcenárium, January 2019, pp. 35

[13] cf. ibid.

[14] “There is just one real thing happening to man in life, and it is death. But it is only a thud. It does not even have time to hurt. Death has no dimension, has no world. It is only the idea of it, its conception, its embellishment and ritualization, in one word, its culture, which may have a world – however, it is just as unreal as anything in human life. Cf. Szilágyi, Ákos: Halálbarokk. A semmi polgárosítása (Death Baroque. The Civilization of Nothing), Palatinus, 2007, pp. 137–138

[15] Barnard-Henri Lévy is currently campaigning with his self-staged mono-drama, Looking for Europe, across Europe, and also met Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán in April 2019.

(08 December 2022)