Now, that it is April 2022 already[1], the directors and dramaturges at our theatre are becoming increasingly interested in the focus of the Theatre Olympics to be held in Hungary in 2023. What is the motto that best suggests the present state of our globalized world? What are the universal concepts by which the mission of today’s theatre can be redefined? The Tragedy staged by Silviu Purcărete at MITEM VII, which took place between September 14 and October 9 last year, may even be considered as the harbinger of the Theatre Olympics because the year 2023 will also see the bicentenary of the birth of Imre Madách.[2] So let us start our regular flash report with this production.[3]

ZSOLT SZÁSZ: New directorial concepts as realised on the stage time and again have always played a primary role in the reinterpretation of the classics of drama literature. What makes Purcărete’s production exceptional is that he had come up with a radically new reading before the rehearsal process: he wanted to stage Madách’s work as a theatre for the parousia, or resurrection. His dramaturge, András Visky has the following to say about the director’s ars poetica in his work diary involving the rehearsal process: “[Purcărete] regards the theater as the stage of universal events: a space where Revelation is achieved and we participate in the administration of justice. Not a theater of illusion, opposed to reality, but on the contrary, the theater of the sole reality, opposed to the world as optical illusion.”[4]

ÁGNES PÁLFI: This salvation history perspective was by no means always characteristic of Tragedy interpretations. If we now re-read György Lukács’s 1955 review in Szabad Nép, which rejects the work on account of Madách’s pessimistic view of history, what we really get shocked at is that the Christian eschatology of the framing first and last scenes is totally out of the question, so it does not even become the subject of criticism. The change of attitude in this field came with the 1999 study[5] by Gábor Pap, who interpreted Madách’s “world drama” focusing right on the first and last scenes within “an astral mythical framework”. However, this astral mythical reading of the vast cycle of time beyond history, which, thanks to Gábor Pap’s lectures, had been well known for quite a long time among receptive young intellectuals, did not attract the attention of contemporary directors. I remember Marcell Jankovics saying at a screening in the late ’90s, when he presented the already completed historical scenes of his animated film, that “as the eclectic child of our eclectic age” he did not find the key to the visualisation of the framing first and last scenes. Not much later, János Szikora came up with a notable concept that was congenial to me: in his staging for the festive opening of the new National Theatre on March 15, 2002, he took a kind of generational perspective when he started and finished the story, the drama of expulsion from the Garden of Eden, with the first couple of people, József Szarvas in Adam’s role and Vera Pap in Eva’s, like two aging adolescents, as if referring to his own “great generation”.

Zs. Sz.: Also, the problem of beginning and end was in the focus of the 1984 film version by András Jeles, when he started and had this story played through with preadolescent children, drawing attention to humanity’s inherent sinlessness, which is given again and again as a chance for successive generations. This kind of primacy may have puzzled Purcărete as well, since we know from András Visky’s diary that he returned to Jeles’s film several times during the interpretation. Yet, in the end, he found the way of staging in terms of genre: “»We’re not playing a parody of Madách – or rather the Tragedy – but a guignol: we seek the amateurism and immediacy of folk theatrics« – he told the actors. If it is the Bible, then let it be the peasant bible, or biblia pauperum; if theology, then a theologia pauperum”, as Visky’s diary has it (p 234). With this in mind, I asked him at the talkback after the performance whether medieval genres like mystery and morality plays could be considered as forerunners of this production[6] – to which Purcărete gave an affirmative answer, but could not elaborate in the absence of time.

Á. P.: This consistent genre perspective gives a unity to the theatrical language of the production, as opposed to the stylistic eclecticism which characterizes the historical scenes in Jankovics and Szikora’s interpretation. Purcărete radically ignores the tools of psychological realism, but enforces the surreal pictorial logic of the avant-garde, which, with its absurd, irrational shifts, reinforces dreamlikeness and liberates the passage between the individual historical scenes. However, it is most understandable that the two Prague scenes – centred on the existential drama of modern European man, including Madách’s personal karma and the painful chapter of his life, the crisis of his marriage – would not work in this unified formal language combining the tradition of 20th century avant-garde and medieval farce.

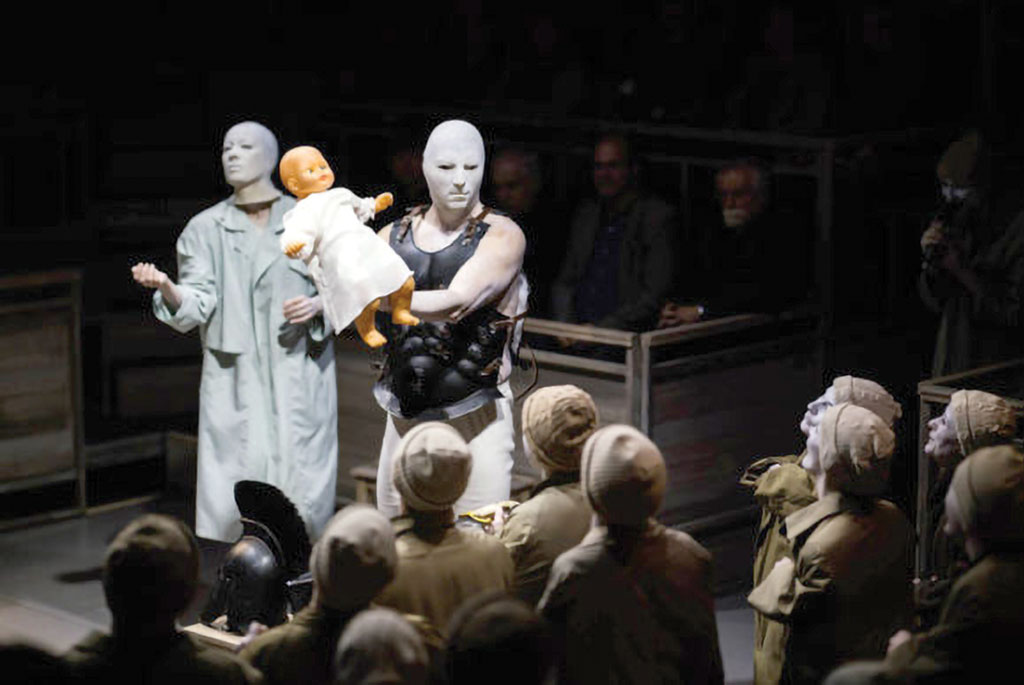

Zs. Sz.: We do not see people in this performance. Almost naked whitewashed bodies move on the autopsy table of the Theatre surrounded by the oval auditorium as well as along the two axes of the cross-shaped playing area, which suggests from the outset that these beings are already inhabitants of the phalanstery. But beyond that, throughout the historical scenes, Adam and Eve are even wearing masks to cover their entire heads, which emphasizes their puppetlike quality once and for all. In every moment we perceive that they exist not only in the borderland of dream and wakefulness, but – as is natural in the case of puppet figures – at the edge of life and death.

Á. P.: The nature and significance of this ambiguity is revealed in the last scene, when following the key sentence of the dramatic climax (“Ah, Adam, I’m in the family way”[7]) the inhabitants of the phalanstery begin to dance slowly in pairs, like the multiplied offsprings and replicas of the first couple. The white lily symbolizing the virginity of Mary in the hands of the expectant Eves suggests that they are all bearing Jesus, the new Adam. Yet, unlike the couple in the Madách drama, they apparently have not awakened to self-awareness from the dream spell that was cast on them.

Zs. Sz.: It is a great challenge for any director to have the Lord’s concluding words rendered at the very end of the work: “I told you, man: fight, trust and be full of hope!” In the production from Timisoara, Enikő Éder and the choir echo this celestial phrase in unison. As mentioned in the interview with the company[8], Purcărete originally meant to have the Lord speak in a child’s voice. Finally, he entrusted the task to Enikő Éder, who, with her atonal speech-voice, conveyed this non-worldly voice of the Lord, always present in the background, as if we were hallucinating the fading voice of a child. However, on the stage of Misericordia, written and directed by Emma Dante, there is only one word left for the “child” at the end of the performance: “mama” – which also has a powerful effect. I wonder why?

Á. P.: It can also be interpreted as when the deaf-mute boy says this first word, which is, at the same time, the final word of the performance, the three foster-mothers, who have previously been caring for him as a backward infant, can now release him into the adult world “in the hope of a better life” – as one of the foster-mothers (Italia Carroccio) put it at the talkback. Still, when we come to think about it, it is not a happy ending, but a cathartic moment that, like in the case of classical tragedies, in fact mobilizes our sense of loss. For the three aging prostitutes are now losing the only meaning of their lives, the common adopted child, just as the boy is being expelled from the paradisiacal state which has been the freedom of dance for him up to now in the world of verbal communication. Katalin Kemény, when she spoke of the original meaning of katastrophe, the ability to turn to reality[9], was probably drawing attention to something that Emma Dante apparently also came to think through when staging this story.

Zs. Sz.: Nonetheless, it is a post-dramatic author’s theatre, but it goes far beyond the sociological criteria that many are trying to embrace here, too: they try to capture the drama of our age in its own brutality, demonstrating that today it is worthwhile to focus only on the stories of marginalized existences or people with disabilities, and that artists must act as protagonists, demanding to directly shape social discourse. In my opinion, the main merit of this production lies in its ability to override this kind of civilization-critical attitude. Without any didactic overtones, the members of the company go through their own life drama to ontological questions about what is the ultimate mover of man as a gendered being. It is no coincidence that Simone Zambelli’s both elementary and virtuoso dance language is discovered and incorporated into the play, which, combined with the emotional surplus of the foster-mothers sassing in their regional dialects, creates the sensual evidence of a fuller reality for the viewer. At this point, it is worth mentioning the influence on Emma Dante of Tadeusz Kantor, who also devoted theoretical writings on how a “poor” ordinary object can become a sign of even Man on stage. The artistic revolution of the 1960s and 1970s had similar issues at the heart and they do not seem to have lost relevance to this day. The two great masters, Robert Wilson and Teodoros Terzopoulos, representing octogenarians at this MITEM, have raised the fundamental questions of theatre again and again for decades. It is a shame that their results could not be incorporated into Hungarian theatre theory and practice in their own time.

Á. P.: Robert Wilson’s theatre was brought closer to me by János Pilinszky’s 1977 book. The poet saw Wilson’s production of Deafman Glance in Paris in 1971 and subsequently made friends with Sheryl Sutton, who had an elemental influence on him as a black, silent and still presence in this piece – the dialogue between the two of them gave birth to this particular Pilinszky volume, one of the most important spiritual foods and cult objects of my generation yearning for a “new sensitivity”. However, it was not until 1994 that the Hungarian audience first saw a Wilson production live at the Madách Theatre. I mention this because being late has turned out to be critical to me several times in my life. I was over forty years old when seeing László Vitéz by Henrik Kemény in Nyírbátor I sighed “had I had this elementary experience at the age of three, I would have become a different adult…” And now watching Wilson’s Oedipus, I felt a similar shock: what could have gone in a different direction if I had encountered this theatrical language as a poet when I was twenty…

Zs. Sz.: The Oedipus performance, which premiered in 2018 and was on at MITEM twice, also reflects how much has changed in Wilson’s art since the ’70s. The production titled Doctor Faustus Lights the Lights, which opened in ’94, is memorable already on account of being the first one the Hungarian audience could see. Yet it is no coincidence that Wilson returned to this subject several times as a director of the great narratives of early modern times. The exceptional format of Oedipus stems from the fact that he has now turned to the mythical subsoil of European drama, which, through the masterpiece of Sophocles, makes all the genre issues of Greek tragedy discussable again.

Á. P.: I had the impression during the performance that in this rendition of his Wilson came quite close to the spirit that we perceive as the ultimate mover of ancient tragedy when reading concrete pieces of Greek drama: all through, Wilson focuses on the relationship to fate, and returns again and again to the very scene which immediately precedes, or follows Oedipus’ murderous act of killing Laios. This text, repeated unchanged in the narration, represents the “bonkers” state we all know when we are recalling the decisive moments of “why it could not have happened otherwise” over and over again in our lives. One further question might be why fate, and the relationship to fate have become so important to Europeans today, 2500 years later.

Zs. Sz.: You have used the Latin word fatum, which means fate and prophecy at the same time. Wilson radically breaks up the Sophoclesian drama structure; so to say deletes the choir, which was meant to maintain the ceremonial nature of the performance on the Greek stage, but he does not even have the prophet Tiresias act as a talking character – his figure is portrayed, otherwise brilliantly, by a woman, an elderly German dancer. He has the story evoked by a Greek actress though, who simultaneously plays – in ancient Greek – the dramatic role of the fortune teller and the chorus, with the overwhelming power of past rhapsodists. Although she speaks in prose, she is able to connect the celestial and earthly spheres with the intensity of dithyramb that appeals to the inhabitants of the upper world. And at the same time as the repetition you mentioned, we see five dancers, Oedipus included, on stage, stepping on large steel plates that make a storm-like, thundering sound at every step, as if releasing the energy inside the material. From time to time in the performance, such elements add up to create the mechanism of action, which, in my opinion, cannot be described in full by saying that it is a technically perfectly executed total work of art production.

Á. P.: At this point, again, it is worth mentioning the concept of techné (τέχνη), which is the foundation of the ancient Greek conception of art, and by no means identical with what in the West is mostly identified today with the perfect technical skills of the artist. Following the line of thought of Olga Freidenberg, who deals with the issue in depth[10], we can say that techné comes into play when the artist is already able to function and create as the medium of the Creator. If the notion of poetic theatre makes any sense [11], the question is worth rethinking by taking the beyond-literary-genres complexity of this production as a starting point. For there is no doubt that the narrator and the dramatic epic, as well as the prophetic lyrical voice of the dithyramb mutually enforce one another on this stage, forming a symbiosis that goes beyond itself.

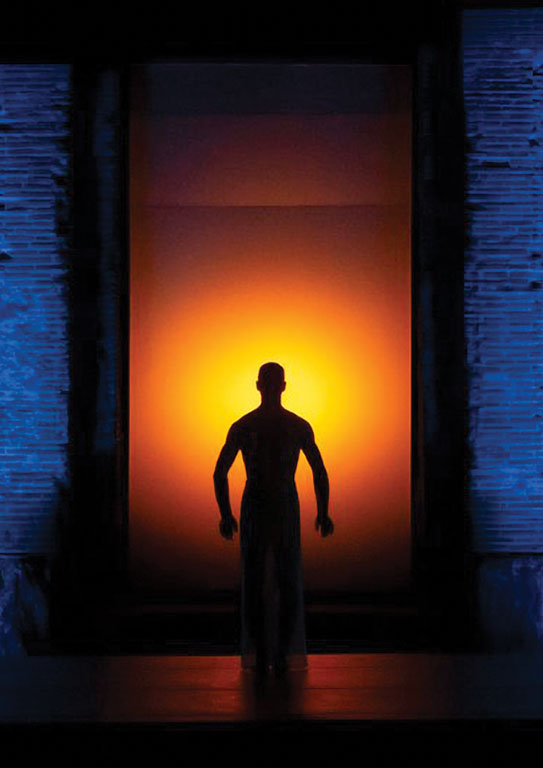

Zs. Sz.: I must admit that I am just getting to know Wilson’s art, too. Although I was sitting there in the Madách Theatre auditorium in 1994, there is only one image that I can recall from that performance: with infinite slowness, a white cube was descending diagonally in the middle of the stage, in sync with a man in a woman’s role, wearing a white dress, with a sickle in his hand, crossing the stage. Then I learned it for a lifetime that slowness can produce focussed attention, which is the most important thing for any theatre practitioner. In the case of Oedipus, it is as if the whole thing was about this focussed attention. The first image already engages the viewer in the meditative space of the performance: when in the middle of the stage a silhouette of a human figure emerges in the pulsating backlight in front of a light source behind the canvas, it is undecided whether it is a man or a woman, approaching aslant or moving away, but we feel that we ourselves are standing there facing the Light in the sustained moment of sunrise or sunset.

Á. P.: Unlike Wilson, Theodoros Terzopoulos is one of those directors who explain their ars poetica in their theoretical writings as well. Szcenárium also published an excerpt from his book, which will soon appear in Hungarian.[12] As with a Greek director, it is almost natural that his performances are related to the ancient dramatic heritage. His production titled Ajax, the Madness is based on Sophocles’ little-known tragedy, but, like Wilson, he does not stage a linear dramatic plot. Based on his writing titled The Return of Dionysus I think this blood-soaked story can be read as in fact a demonstration of the creed and working method of Attis Theatre on the pretext of Sophocles’ play: “We were trying to provoke the uprising of deeper forces, to tear down the walls which were keeping us immersed in ourselves, to bring forth images from the space of the unconscious, to fly out of our known limits. We realized that our duty is to make the people our accomplices and let them be our partners in the long journey to the country of Memory, the country which hides the primary body and the primary language”.[13]

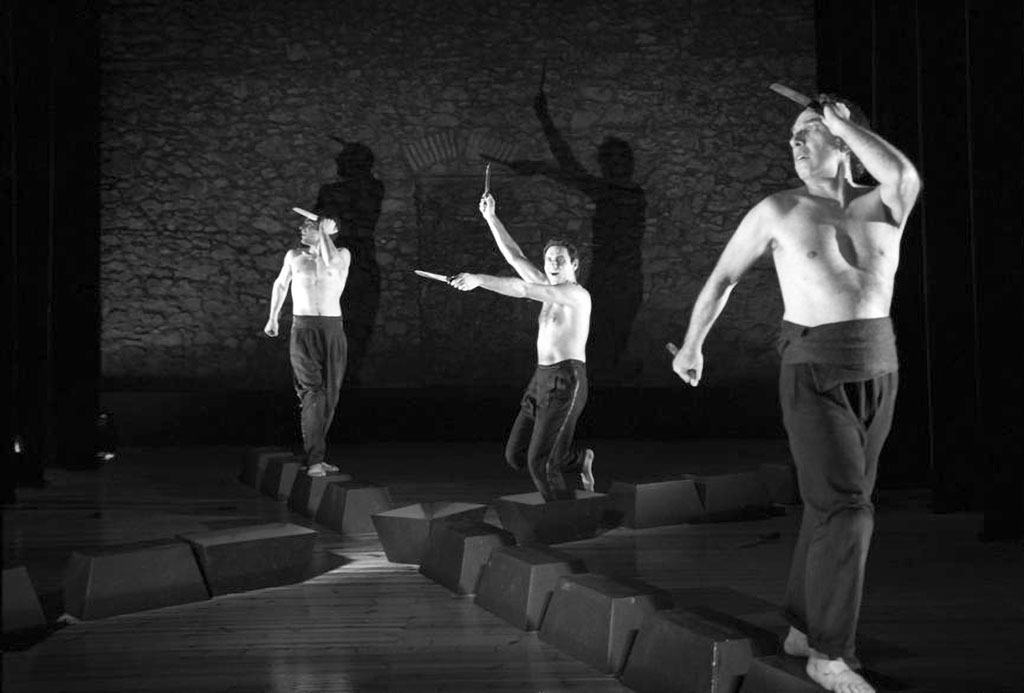

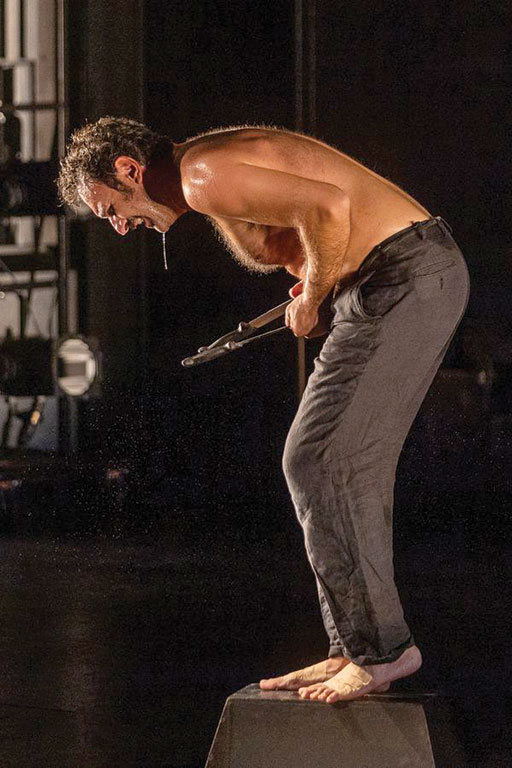

Zs. Sz.: The study you quoted was published by Terzopoulos in Greek in 2015, and the production itself has been on the repertoire of Attis Theatre since 2004. At the talkback after the premiere, the director himself spoke about the fact that it was meant to be a kind of workshop study rather than a full-length production in its own right. Yet I would turn your question around: What is it that has been keeping this barely one-hour production alive for 17 years now? After all, the world has changed a lot since then, and, let us face it, passing time has not been kind to the actors in the physical sense, either. If we click on the photos taken during the performance, we will see young male bodies brimming with power, which prove without words that in this theatre workshop the energy liberation mentioned in the text you have quoted above has indeed taken place.

(photo: Zsolt Eöri Szabó, source: nemzetiszinhaz.hu)

Á. P.: With this former performance, which we unfortunately did not see, it is easier to associate the Brechtian attitude inherent also in the new handbill to the production: “…the performance is a study upon war’s paranoia, violence and blood. The actors describe the criminal acts of Ajax, they are identifying with them, embody them and finally are transformed victims-victimizers, behaving with the same lethal mania that possesses Ajax.”[14] Referring back to my previous suggestion, I think the director expresses here that it is far from hazardless to “provoke a rebellion of deeply dormant forces”. As far as Brechtian aesthetics is concerned, I have been preoccupied for decades with the beginning of Illyés’ Bartók poem dated 1955: “»Hangzavart?« – Azt! Ha nekik az, / ami nekünk vigasz!” (“»Discordance?« – Yes! If it is that for them / which is solace to us”), then came the expeditious answer to this poetic question: “Ím, a példa, hogy ki szépen kimondja a rettenetet, azzal föl is oldja.” (“Here is the parable: / As you articulate the terrible, you dissolve it.”) I believe I am discovering the same ambivalence or even paradox in this one-time cult poem, as Terzopoulos describes the “ecstatic god” of theatre, Dionysus, who “… represents mutually exclusive and intertwined identities at the confines of god and animal, insanity and rationality, order and chaos.” How can we comment, recalling our experience of Ajax, the Madness, on this paradox today, in 2022?

Zs. Sz.: One thing is for sure though: we see actors on stage, no matter how old they are. First we see them standing on black coffin lids laid in a cross shape on the floor of the playing area. Meanwhile, we can hear Sophocles’ text with the messenger reporting how Ajax killed the flock of sheep and the shepherds after the unjust decision, believing them, in his madness, to be his opponents. The play begins while the text is being repeated three times, almost without change, by all three actors respectively. The actor who is just speaking is holding a knife with both hands, imitating a frantic run in his standing position. His whole body is trembling. In the meantime, the other two companions are relocating the coffin lids, then explore their interior – each one is blood red: these are the contracted symbols of killing and life, death and the cradle. The beginning and the end are simultaneous – like in Wilson’s Oedipus or in the poem titled Semmi himnusz (Nothing Hymn) by the contemporary Hungarian poet Noémi László, published in 2004: “… Mintha az előbb volna az után. / Mintha túl volnék a haláltusán / s innen azon, amibe belehaltam. / Mintha keresztül suhanhatnék rajtam / és mindenen, ami feléled. / Mintha belélegezhetném a mindenséget.” (“It’s as if before was after. / As if I was beyond the agony / and inside of what I died of. / It’s as if I could glide through myself / and everything that is waking. / It’s as if I could breathe in the universe.”) So we are probably in a watershed moment when our perception of time and space is undergoing a fundamental change. On this stage everything is utterly laid bare, root extracted. Symbols may change, knives may be substituted with bards and red patent-leather heels, which serve as the same killer weapon or handgrip as knives used to. The viewer’s subconscious is influenced by killing and erotic desire, the two great movers, simultaneously. Seeing the aging actors, we feel that they, as sentry spirits, still represent everything that constitutes the foundation and essence of European cult- and cultural history. Which, in the end, can be simplified to what Terzopoulos said in the film representative of his oeuvre, The Ritual Theatre: martial dance on the male side, and mourning on the female one constitute the two upholding dramatic rituals in folk tradition.

Á. P.: In contrast, the other Terzopoulos production, Alarme, which opened in 2010 and unfortunately few of us have seen, examined the nature of female hysteria, revealing in almost microscopic detail the threatening state of existence when two women face each other, and their struggle becomes unstoppable. Same-sex competition in adolescence is absolutely appropriate, as the battle for dominance then serves self-knowledge as well as socialization for both boys and girls. Here, however, we see the murderous rivalry between two adult women, which, when viewed from a specific historical situation, takes place between the two queens, Elizabeth and Mary Stuart, for power. Yet, beyond gaining earthly power, this unstoppable hysteria apparently has its roots deeper. The pictorial language of the production makes concrete reference to certain mythologemes, too.

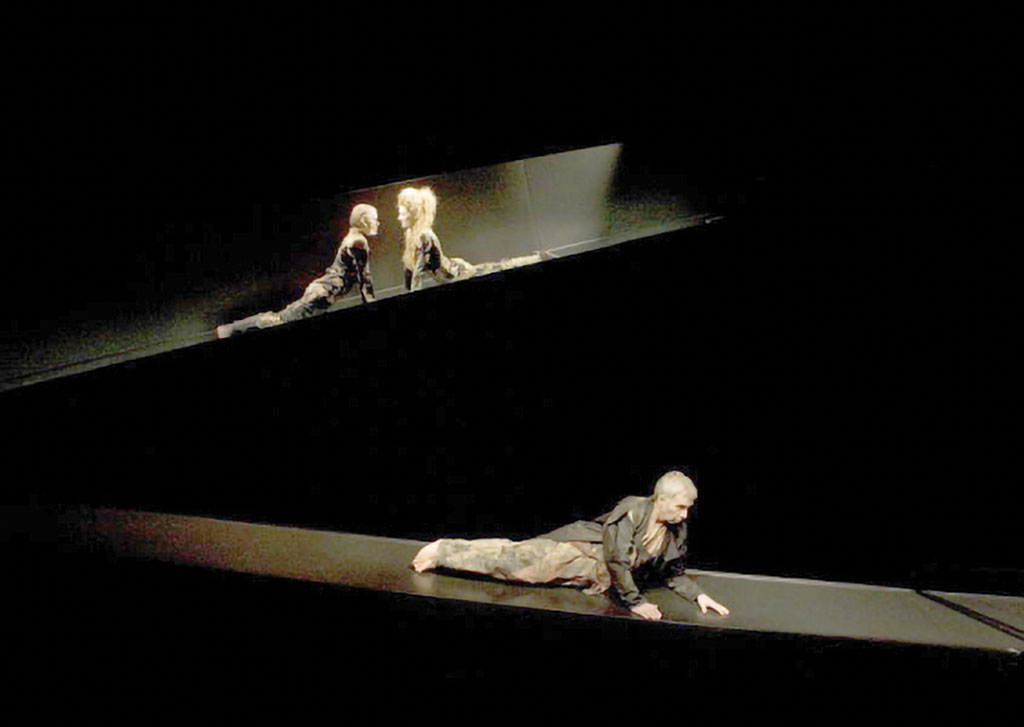

Zs. Sz.: There is no need to decipher symbols to notice that there are two snakes fighting each other on this stage: we can concurrently feel their fierce struggle, as well as their urge to intertwine. The set of two large space elements also guides our glance by starting from the top, from the right rear half of the stage, to the front and to the centre each time, and then the same way backwards, following a continuous snake movement. In the tilted cavity of the sloping wall plane at the back, Elizabeth is descending facedown from the right, while opposite her, Mary Stuart (the defeated queen) is crawling upwards from the left, from below. While a man (who, according to the playbill, is an impoverished nobleman) is also moving on his stomach along the piste which stretches into the middle from the left. If we just stick with the snake, which has countless mythical connotations, one of the most archaic stories came to my mind at the climax of the performance. It is the myth of the ancient snake that swallows and regenerates the Sun as the world – showing that in the midst of their never-ending battle of words, these two “snakes” are unable to either swallow or spit out the golden disk that symbolizes the universe. They only keep serving it into each other’s mouths to silence the other one by it for a while.

Á. P.: The filthy comments of the “snake man” target precisely this barren verbalism, apparently referring to the general state of the world, which, at the same time, may be interpreted as a kind of critique of feminism. The performance as a whole envisions the hopeless situation in which both woman and man find themselves outside the cosmic medium of creation and cannot find their way back to the instinctive and ecstatic state of fertility which has given birth to and operated European culture until very recently.

Zs. Sz.: The next performance we want to talk about is the production by the György Harag Company of the Szatmárnémeti Északi Színház (Northern Theatre of Satu Mare), Rasputin, which deservedly had one of the greatest successes at this festival. But before that, it is worth referring back shortly to the historical background of the basic situation of Alarme staged by Terzopoulos. Why did the director’s choice fall on these two female monarchs, Mary Stuart and Elizabeth I to portray the communication crisis of our time? Probably because their correspondence, in which they both constantly refer to Christian love, was in fact also a kind of religious polemics between the prominents of the contemporary Catholic as well as the brand new Anglican Church. Which, from a European perspective, began with Luther’s appearance in 1517 and culminated 100 years later in the bloodbath of the Thirty Years’ War, which can even be considered World War Zero. This is worth putting forward here because Géza Szőcs, the author of Raszputyin küldetése (The Mission of Rasputin), raises the “ahistorical” question of how Europe could have avoided World War I, which had already projected the second one.

Á. P.: This play can now be regarded as Géza Szőcs’s last will and testament, through which he is sending a message to the future; that may be the reason why he urged its translation into as many world languages as possible.[15] Director Sardar Tagirovsky related the dramatic material even more to the current state of the world. It is not for nothing that – in an interview with him – he refers to the new global system of Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg, Metaverse, which he says is threatening with the horrors of a “historical-scale digital regime changer”[16]. He also mentions Madách’s Tragedy in this regard, saying that perhaps we are already beyond the “phalanstery reality” envisaged therein[17]. The parallel between the two pieces does not indeed seem exaggerated after we saw the performance. Expressly or tacitly, it implies that a contemporary Hungarian playwright or director may also take the world stage by raising their own questions concerning philosophy of history. This self-awareness can also be perceived in what could be understood as Sardar Tagirovsky’s ars poetica: “I, as a director, have been interested in how we can flip this historical situation, which rhymes with our current condition, so that we can present our fall in Europe as a kind of survivor stunt, a theatrical event amounting to victory”[18].

Zs. Sz.: The final images of the production are indeed worth mentioning in concrete terms. Think of the bombastic operatic scene with Rasputin’s death and the several attempts to kill him in the Yusupov House as its themes. The full spectrum of the theatrical language of the performance unfolds in connection with it. Still wearing a black cassock, Rasputin, the only one whose face is not masked in white, is recalling cheerfully yet resignedly, as if at his own funeral reception, his unsuccessful attempts with European rulers to prevent the outbreak of war. Parisian courtesan Loulou, who is meant to symbolise the inherent purity of art with her indispensable symbol, the violin, is making a reappearance. Another young woman, Guseva also emerges, presumably from Rasputin’s past in Russia, who, as an angel of death, is held captive here by the hysterical desire to kill and embrace at the same time. This duality is symbolised by the oversized knife that she nails alternately to her own loins or Rasputin’s throat during their “intimate” duet. Such an exaggeration and overemphasis of objects unequivocally points to a puppeteer’s approach [19]: its role is to show Rasputin as invincible and immortal, parodying the absurdity of stage death. A phenomenon who, unlike the puppets complying with the so-called “historical compulsion”, is inspired by an archangel conveying the command of Heaven, and who may be said, despite his fall, to have tried to fulfill its mission to save humanity at the cost of its life. Nevertheless, Rasputin is not a tragic hero in the literal sense of the word – inviting him onstage is to the aim that we do not lose our historical memory. This is served by the more than three hundred texts inserted, which – apart from enriching this great narrative with philosophical treatises and Rasputin’s internal meditations – provide a wealth of additional information about the historical events and characters invoked on the stage.

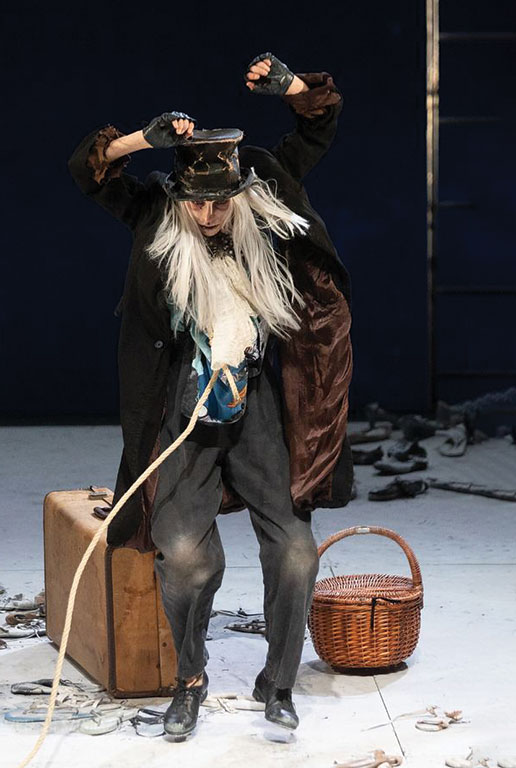

Á. P.: Well, after the drama by Géza Szőcs, I think we had better continue this conversation with Beckett’s absurd play, Waiting for Godot, which, as we know, was written in French in 1948/49[20]. If one reads the text carefully, they will find a number of clues that make up the picture, namely that it is with full intent that the characters in this drama choose to retreat and to escape the trauma caused by World War II. We may as well put it like historical amnesia in their case amounts to a kind of rebellion. However, the larger-scale dimension of salvation history opens up to them exactly by virtue of the cosmic exposure stemming from this exodus, which is actually made clear in the beginning by the dramatic situation in Waiting for Godot. And if we recall the famous verse of the Gospel of Mark: “Therefore stay awake – for you do not know when the master of the house will come, in the evening, or at midnight, or when the rooster crows, or in the morning”, there is no doubt about a concrete parallel here with the anticipation of the second coming of Christ[21]. Putting this Biblical situation into the centre can only be the result of a deeply thoughtful and conscious decision on the part of Beckett. Just like that his figures undergo this situation without being aware of it, and they keep looking upon Godot as the mysterious object of their longing all through. This unconscious dreamlike existence reminds me of the final image in Purcărete’s direction of the Tragedy, in which the multiplied figures of the first couple have apparently not yet awakened from the dream Lucifer cast on them.

Zs. Sz.: The kind of parousia interpretation that Purcărete represents in this staging of his could be extremely fruitful for theatre practitioners in the future. It also anticipates rethinking the very nature of acting, too, if you like. The most recent trends in aesthetics are now treating actors as mere moving bodies (see the term “biological setting”). It is probably also the reason why contemporary theatre wants to get it over with the Beckett phenomenon itself, because if the underlying contents of the dialogue between the two figures is comprehended to a lesser and lesser degree, it is easy to arrive at a reading where this all boils down to a pointless and meaningless quibble.

Á. P.: This aspect also has its own raison d’être, if by it we do not mean the ordinary reading of the average viewer but, instead, think of the crisis of communication that the world-famous semiotician, Lotman called attention to more than three decades ago: “We are interested in communicating with the very situation that makes communication difficult and ultimately impossible.”[22]

Zs. Sz.: When sitting in the auditorium, I could palpably feel the visceral resistance of the audience, “Oh dear, a new Godot yet again”. And I must admit that I was also running Szilárd Podmaniczky’s paraphrase parallel with this performance, which was on at the RS9 Theatre from 2008, with a super cast and the telling title Waiting for Becket, and which asked straightforward questions about the actor’s existence. But then contact between the auditorium and the stage became more and more lively during act two. I think it was because these excellent actors know exactly what it means to embrace a stage self and to create the drama of intermediate existence internally, the gateway between their civil selves and their role selves, which will then inescapably captivate the viewers as well.

directed by Gábor Tompa, Maria Leite as Lucky

(photo: Zsolt Eöri Szabó, source: nemezetiszinhaz.hu)

Á. P.: Gábor Tompa asserts in an interview that this very game for survival has been at stake in this umpteenth Godot rendition of his, thanks to which it is, after all, not a gloomy performance he says. He even goes so far as to say that “despair is the highest degree of hope”.

Zs. Sz.: Well, I would argue with this conclusion of hope, because I can vividly remember Kantor’s lesson in which Death is the ultimate point of reference. For me, the most shocking part in this performance is Lucky’s Dance of Death, which overrides the moral philosophy-based dichotomy of hope versus hopelessness. It was at least as powerful as the dance in Misericordia of Arturio, who is also referred to by the foster-mothers as Pinocchio.

Á. P.: Yet beyond that, the couple Lucky and Pozzo is also a metaphor for the agony of European civilization. It is a similarly brutal formulation of the madness in the exercise of power as well as the pathological relationship between the prisoner and the prison guard to what we see in the great narratives of the Enlightenment, that is Candide by Voltaire or Gulliver by Swift. Also, it is no less important that without this couple being around, the dialogue between Estragon and Vladimir would turn pointless and the drama lose its dynamics. Through them, the “real world” breaks into the world of the two “stage selves”, demonstrating that retreat or escape is ultimately impossible.

Zs. Sz.: Ivan Franko National Academic Drama Theatre, Kiev, featured at last year’s MITEM for the third time. The first piece of the trilogy by the Ukrainian national classic Panas Mirny, Limerivna, was staged by Ivan Urivsky, one of the most prominent representatives of the new generation of Ukrainian directors. Calling to mind the production which we saw in 2019 (Morituri te salutant), directed by Bogomazov, what I find as the most striking thing is that this performance also seems to be worded in the same stage language. The background to it may be that the creative intelligentsia of this young nation state has, for generations, been trying to create a unique stage language which feeds on its own folk traditions before all else. The symbolic sign of the final image, the straw puppet made to dance, which evokes Wyspiański’s The Wedding, indicates the importance to the director of the common mythical conception and cultural code of this Central European region, which intermingle the cult of ancestral spirits with archaic rites promoting fertility.

(photo: Zsolt Eöri Szabó, source: nemzetiszinhaz.hu)

Á. P.: I think that this final image of the performance was, at the same time, the turning point which placed this karmic story with a melodramatic tinge or modern ballad involving a test of fidelity, into another dimension. Without that, the story would be little more than the individual tragedy of two young lovers who proved weak against the force of circumstance. However, this frozen moment concluding the story, the rupture of the female protagonist’s heart, did not in its style evoke either the sentimental topos or the well-known formula of folk poetry, but presented the almost passionate and romantic gesture of a heroic life sacrifice. I venture to say that this scene, shocking even in its austerity, may actually be associated with a vision of the death of a nation. Yet, without the appearance of the straw puppet, this change of altitude could hardly have taken place.

Zs. Sz.: The appearance of this animated straw puppet as an independent actor can only be interpreted and justified together with the materials and tools used in the performance. The story takes place in a traditional peasant world, where everything revolves around the production and accumulation of grain, wheat and material goods. In the empty and neutral stage space the scenery is also a bundle of straw, and the villagers’ choir and the talking heads turn into cabbage heads from time to time. The solemn end is the counterpoint to this consciously constructed grotesque and surreal use of signs. The dramaturgy of the performance is permeated by the puppeteer’s approach. Namely by that the living and the dead status – living and dead objects – are convertible at any time. This, in turn, evokes a more comic effect, rather than reinforcing the sympathy and emotion characteristic of melodrama. However, the performance as a whole, and the vitality of the company had a cathartic effect on me. This vitality is broken by the death of the best, the most beautiful and innocent girl.

Á. P.: This staging reminded me of Plato’s dialogue, Symposium, in which one of the speakers, Phaedrus, claims that civic virtues – courage, fighting spirit and morality – are also attributable to Eros: “And if there were only some way of contriving that a state or an army should be made up of lovers and their beloved, they would be the very best governors of their own city, abstaining from all dishonour, and emulating one another in honour; and when fighting at each other’s side, although a mere handful, they would overcome the world.”[23] The typical storyline of Hungarian folk tales is also founded on the idea that the weakened kingdom can only be restored by the lovers who are meant for each other. Wyspiański’s The Wedding is also grounded on this “archaic” conception. “Marry a peasant girl!” – this nation-building programme of the young generation at that time was nourished by the belief that at the beginning of the twentieth century Poland would be born and from her dust shall she arise as a result of the wedlock of the intelligentsia and the peasantry. However, the play accommodates a warning as well: on the night of the wedding, the straw puppets – the spirits of the long-dead ancestors, the spirits of noble Poland – also pay their respects! Many people today believe that love, the last myth of humanity, is a thing of the past. Yet the unbroken popularity of the type of drama typical of the bourgeois era, and of Chekhov’s plays in the first place, are proving just the opposite.

Zs. Sz.: The view that Chekhovian dramaturgy is a model of bourgeois drama has indeed been widespread in the Hungarian reception. Still, if we take a closer look, Chekhov’s heroes are not urban citizens, but impoverished rural landowners or marginalised intellectuals. Therefore they can represent neither traditional folk values nor modern bourgeois values, although they, as heirs of Pushkin’s heroes, are receptive to both, and are even bearers of the literary language which yielded, like in Hungary, the basis of nation formation in the 19th century. However, at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries, this way of speaking already proved anachronistic – it does sound funny out of the mouth of Chekhov’s characters, too, just as if they were reading from a book. Nonetheless, this kind of humour was hard to come by on Hungarian stages. Chekhov was played in a kind of sentimental and nostalgic tone until very recently, which greatly hindered the discovery of the novelty value in this dramatic oeuvre.

Á. P.: Honestly, I was very surprised to see that Gorky’s piece which is reckoned to be reminiscent of Chekhov, Children of the Sun, has recently been staged in several Hungarian theatres. I would also be interested in how. In my view, the greatest virtue of Roschin’s interpretation is that he makes absolutely the most of the Chekhovian comedy you have been talking about. I remember well when he said at the talkback after his previous brilliant production, The Raven at MITEM 2016, that as a young director he devoted twenty years to mastering the theoretical work of the two pathbreaking early-20th-century Russian masters, Stanislavsky and Mayerhold, in order to synthesize the two kinds of methods they had developed. This performance is, in my view, a style parody of these two methods, while it also depicts the drama of the inherent duality of human mentality. I had the impression that these characters on stage, above all the female ones, are in fact infantile adults who have not yet managed to find the object of their love, but are so eager to do so that they begin to hysterically produce the symptoms of passionate love; then the very same persons suddenly change their style and start to organize and instruct themselves cool-headedly, regarding mating as a kind of erotic and purposeful role play. And the actors present it all so smoothly and effortlessly that I think some of the viewers inevitably recognise themselves. I must admit that I was also reminded of my adolescent torments, when I stayed quiet most of the time, unable to find my own language and manner of speaking.

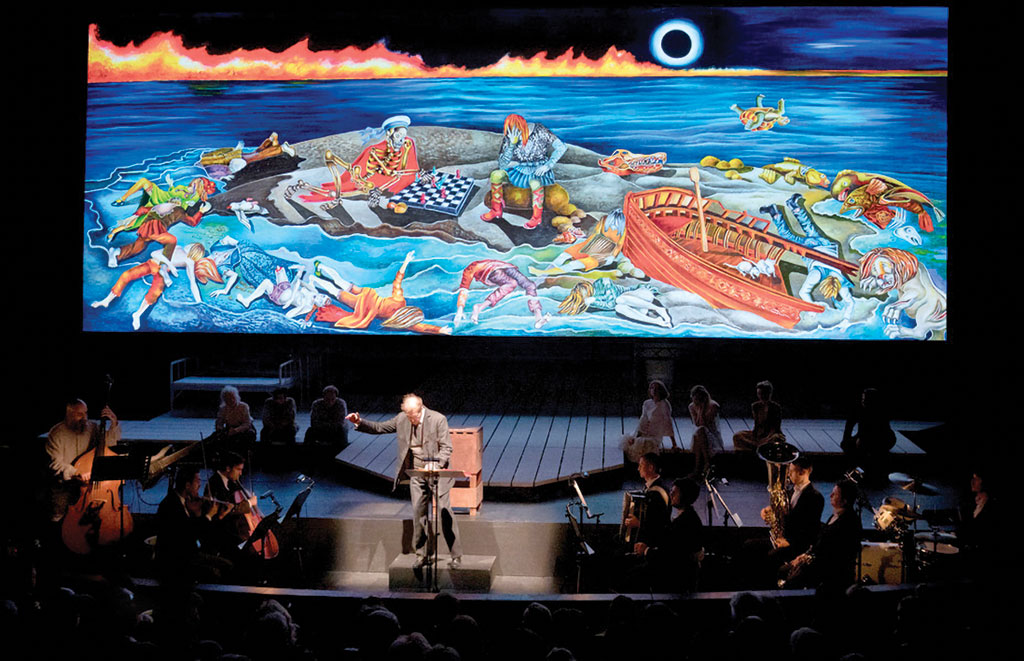

Zs. Sz.: It was also mentioned at the talkback you referred to that in the second decade of the 21st century the suggestions that were made during the Silver Age of Russian poetry in the early 20th century are still valid. That period of Russian history is, at the same time, the period of the collapse of the Tsarist Empire. This piece by Gorky was created in the year of the 1905 revolution, but it was also the year when the Russian-Japanese war ended in a Russian defeat. Contrary to the rural locations of Chekhov’s dramas, the characters here are members of the urban lumpenproletariat and idealistic intellectuals living in city blocks. Roschin’s open-plan stage is at once like the deck of a capsized ship or a nursing home, but – because of the row of lamps hanging from above, turning on and off – one might as well think of a shelter where all sorts of existences have been forced together. The only “comfort” device in this stark space is a bathtub, which is the refuge for the wife estranged from the amateur chemist Protasov, who experiments with the synthetisation of homunculus. Several of the intellectuals are making an attempt to take a dip in this lukewarm water, while the audience is listening to fragments of their world-saving ideas and trying to follow their tangled emotional relationships – only to soon realize how hopeless it is, and, instead, start focusing more on the burlesque choreography. At the end of the play, Gorky even unleashes a cholera epidemic on these figures to demonstrate the elemental destructive forces from the outside world. On Roshchin’s stage it is not the epidemic that puts an end to this collective squirm, which can be interpreted as a game that has lost its purpose. The director employs a radical change of image: there is an orchestra emerging from the trap in front of the curtain coming down, and the protagonist, Protasov in his new role is conducting the opera tutti of the last judgement. We see three projections in a row: the ship of life on the way to the new world, and then the shipwreck; next the destruction of the passengers and happy couples in love, with Death playing chess over them in the red setting sun; and finally a huge hammer striking the anvil – an unequivocal symbol of the coming dictatorships.

Á. P.: It is in fact the current situation of the world that is qualified as apocalyptic by this ending of the production which premiered in 2021. Attention is drawn to the vulnerability of the bubble which makes one feel safe for a little while, thanks to the benefits of civilization. And to how frail artists themselves are, too, in deciding whether they are supposed to burst this bubble, which is in fact sustained by themselves, if the situation demands it. In the light of the current war conflict, this direction by Roschin may at least give rise to some hope for the future: it proves that the sense of danger and responsibility within the best of the Russian creative intelligentsia has remained unbroken.

Zs. Sz.: In Hungary, labouring the point of social responsibility has been the loudest voice in connection with the renewal of the theatrical language on the part of left-wing liberal theatre makers for at least a quarter of a century. The middle generation now in their fifties is trying to reinterpret the classics in terms of this programmaticity. Yet how far can one go in this kind of “language renewal”? Are classical authors still adequate for staging today’s drama, by or with reference to them? – On leaving the Hungarian State Theatre in Cluj-Napoca after A Doll’s House performance, I asked myself the question: are Ibsen and the dramaturgy of bourgeois drama still valid?

Á. P.: With this production, director Botond Nagy and dramaturge Ágnes Kali do not address this question, but try to demonstrate that female emancipation is still the most pressing issue today. And there really is no denying that technical civilization is pushing more and more violently into people’s private lives as well, so much so that the aural overkill of techno-music and the unstoppable flood of images doom relationships to failure from the outset, making intimate dialogue impossible. At the same time, it is a completely new situation, which has little to do with the state of the world depicted in the original drama. It is no coincidence that at the end of the performance, rising from her glass coffin, Nora like a disciplined schoolgirl, in the hush that suddenly fell, repeats as a foreign text the famous monologue of Ibsen’s heroine, which is the creed of the new person, the woman seeking emancipation, formulated in the late 19th century.

Zs. Sz.: In their manifesto published in the programme of events, the creators themselves report that the new creative generation is experiencing this crisis in a kind of hypnotized state, a coma which is at least as difficult to escape from as to break out of the compulsive yet comfortable framework of the former bourgeois way of life.

Á. P.: That said, I still consider it an important question whether, and to what extent this production may still be considered an Ibsen play. Or is the author’s name really just a trademark in this case? Nevertheless, as regards Bogomalov’s direction of Crime and Punishment (Priut Komedianta, Saint Petersburg), it is a matter of staging a Dostoevsky novel which has lost nothing of its relevance since its birth. Does man have the right to destroy even a malicious being to take the first step on the path to becoming a great man? Or are only former and present gods, religious founders and warlords predestined and able to do so without a psychological collapse? – This staging professedly reckons with the key questions of Raskolnikov in the novel, as well as with the one whether, after committing the murder he intended to be a “probe”, in possession of what existential experience he is trying to redefine his own beyond morality creed.

(photo: Zsolt Eöri Szabó, source: nemzetiszinhaz.hu)

Zs. Sz.: However, in the case of Dostoevsky’s Raskolnikov, this beyond morality creed does not mean that he is “out of the zone of ethical and moral grind,” as the director put it in the official MITEM programme guide last year. In this performance, cold rationalism reigns programmatically indeed, with the protagonist staying psychologically passive throughout, and this characterizes the acting style of the other actors as well.

Á. P.: The director’s concept is unmistakable from the first scene, as we are listening to Raskolnikov’s mother’s passionately presented voluminous letter, while its contents – a detailed description of the family’s existential constraints – is able, even so, to convey the dramatic ammunition which can throw Raskolnikov off balance and move him from his coffin-like lair.

Zs. Sz.: A memorable episode of this guest appearance was, however, the scene in which the head of the Investigation Department, Porfiry was acting as a simple police constable, unfettered and jovial, with Raskolnikov, smuggling humour and colour into this depressingly monotonous performance. Much to our surprise, this actor, Merited Artist of the Russian Federation Alexander Novikov revealed at the talkback that he had made a heat of the moment decision that evening, for the sake of the Hungarian audience, to go against the director’s instructions which dictate a hibernated style of acting.

Á. P.: So it is far from certain that this production concept, cultivated by many directors today, will be long-lived on contemporary stages. After all, there are more promising alternatives as well, like Slava Polunyin’s smash at MITEM 2019, Snow Show, presented in cooperation with Fővárosi Nagycirkusz (Municipal Circus, Budapest). It also showed that co-arts may play an ever-increasing role in the renewal of theatrical language. And just as in the last third of the 20th century physical theatres had a fertile effect on the toolbox of dramatic acting, now the so-called popular entertainment genres, long exiled from the high arts, are claiming their place among the programmes of prestigious international festivals. A good example of the interaction between these genres is the production Bells & Spells by Victoria Thierrée Chaplin and Aurelia Thierrée, of whom I think that the ars poetica they represent is not only an alternative to a new kind of theatricality, but a conscious and powerful rebellion in defense of the freedom of the artist and art.

Zs. Sz.: This kind of theatre can be traced back to the genre of the once flourishing variety show, which is characterized by a loose garland of subsequent magic tricks, dance inserts, couplets and chansons, as well as scenes of ventriloquists and puppeteers. The separate parts, like in the cabaret, are connected here by the compere, and it is also his role to reflect on the rapidly changing world: he is making fun of the current anomalies of public life, the excesses of politics, the “benefits” of technical civilization, the disintegration of the traditional frameworks of life, and the absurdities of the new lifestyle. At the same time, the variety show of the previous century was also a kind of “bubble” that served as a temporary refuge for an audience recruited from urban middle-class citizens. Still, considering the chances of the renewal of theatrical language, it is also worth mentioning the European theatrical avant-garde, which grew out of the same mixed-genre subsoil in the early 20th century – in the spirit of shocking the public.

(photo: Zsolt Eöri Szabó, source: nemzetiszinhaz.hu)

Á. P.: However, the style of Bells & Spells is not characterized by rebellious avant-garde loudness. This performance unfolds the richness and poetry of the artist’s inner world, making our imagination soar all the way to cosmic spaciousness. The dramaturgy of this poetic picaro becomes coherent without the creators trying to fabulise a traditional storyline out of the separate parts.

Zs. Sz.: I would like to highlight the craftsmanship-like nature of the performance. Behind the brilliant illusionist Aurelia Thierrée and dancer Jaime Martinez acting downstage, like in a puppet theatre, four artists keep the myriad objects, spatial elements and requisites animated in constant motion in the acting area of the great stage, minimizing the use of electronic modern stage technology. This leads to our perception of the imaginary world in its objectified quality as a transformable reality on the one hand, and to our impression of the material world as humanized and transcendental on the other. This kind of animation appeals to the child within us who still walks freely between the worlds of dream and wakefulness, imagination and reality. As you have just put it, it is indeed a rebellion against the increasing aggression of virtuality – it is, as you please, the freedom struggle of the homo ludens in a world where today’s Noras are helplessly trapped in the captivity of their delirium which keeps suggesting the supremacy of the outside world incessantly.

Á. P.: At the beginning of our conversation, in connection with Robert Wilson’s production we already mentioned János Pilinszky, the hundredth anniversary of whose birth was commemorated in 2021. At the heart of this lyrical oeuvre is the trauma of the Holocaust, and the same theme dominates the poet’s theatrical experiments, too. In addition to drawing from Pilinszky’s emblematic poetic texts, the director of Éjidő (Nighttime), Kinga Mezei also tries to rethink the poet’s efforts to create a new dramatic language. Relating to this production, it would be worthwhile to reconsider above all the issues concerning the nature of the so-called “poetic theatre” and the raison d’être of the theatrical representation of poetry – but this is not possible now.[24]

(photo: Róbert Révész, source: szmsz.press)

Zs. Sz.: On another note, I think it is important to accentuate that this production from Magyarkanizsa, Serbia, was made at the Regionális Kreatív Műhely (Regional Creative Atelier), which was founded by the world-famous Josef Nadj / József Nagy and has been spearheading experimental theatre endeavours for decades. In terms of its professional quality, this production is also worthy of the eminent Hungarian theatre workshop in Vojvodina. And as a puppeteer I can say that, similarly to the Bells & Spells production, the creators have brought into being a perfectly animated stage world here. The craftsmanship-like quality is an absolute virtue of the performance, too. But whereas in the case of Bells & Spells we perceive an ever-expanding and cosmic-scale medium, everything in the cube-shaped stage space of Éjidő (Nighttime) acts inwardly, condensing the unspeakable traumas of minority existence and the two South Slavic wars, while digging deeper and deeper into the pits of memory. The greatest benefit of this enterprise does not really lie in the attempt to theatricalize János Pilinszky’s poetry, but in bringing to the surface the collective subconscious realms which make the past of this cross-border area inhabited by Hungarians existent. Particularly memorable are the dreamlike depiction of the dead ancestors as well as the closing puppet scene of the performance, the village wedding, which symbolizes the vitality of a self-renewing community as the counterpoint to the notion of a sinking world.

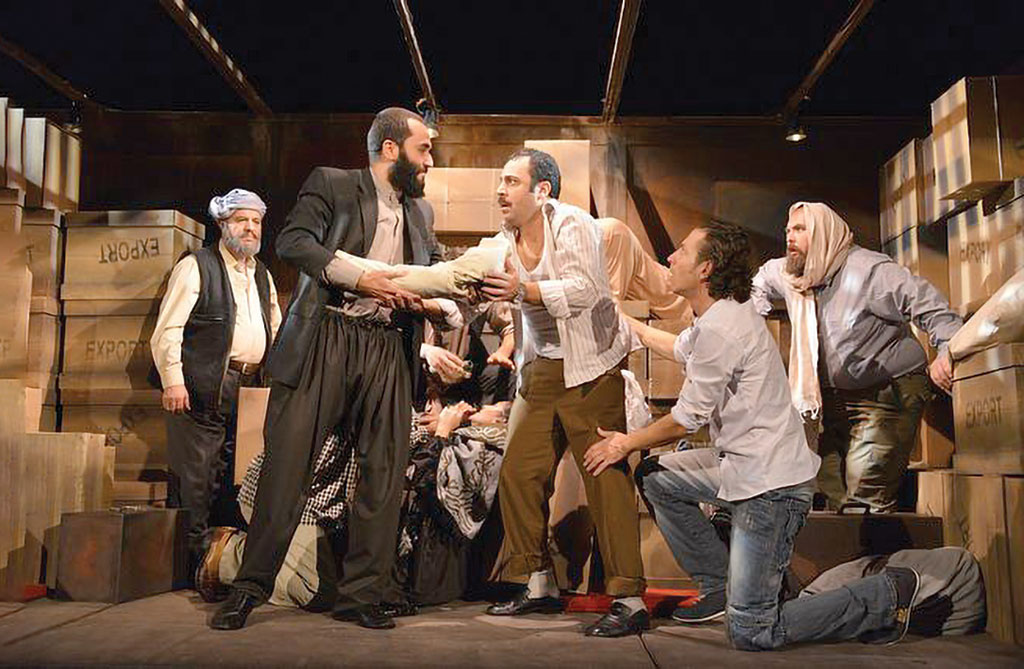

Á. P.: While sitting in the auditorium during the “one man show,” a performance written and directed by Omar Fatmouche from Algeria, I found myself as embarrassed as at the first MITEM in 2014, watching the production titled Where To? by the Ankara State Theatre. For the stage language in which they spoke seemed not only different, foreign, but naive and rudimentary as well. On looking back over eight years now, however, I must admit that the Turkish ensemble left a lasting impression on me, and it is not just so because a year later we got first-hand experience of modern-day migration, which had been the topic of the performance. Actors in the role of illegal immigrants on their way from Turkey to Germany represented a wide variety of people: Kurds, nomadic pastors, including a holy old man, a barber and a mother with small children. Locked together in the cargo hold of a truck, they brought close to us at the level of elementary gestures such norms, values, surplus energy, spontaneous conflicts, and unwritten rules of coexistence within a culture as we had no idea of. It is a good thing that we got intimately close again to a little-known culture and mentality through this “one man show” at the last meeting.

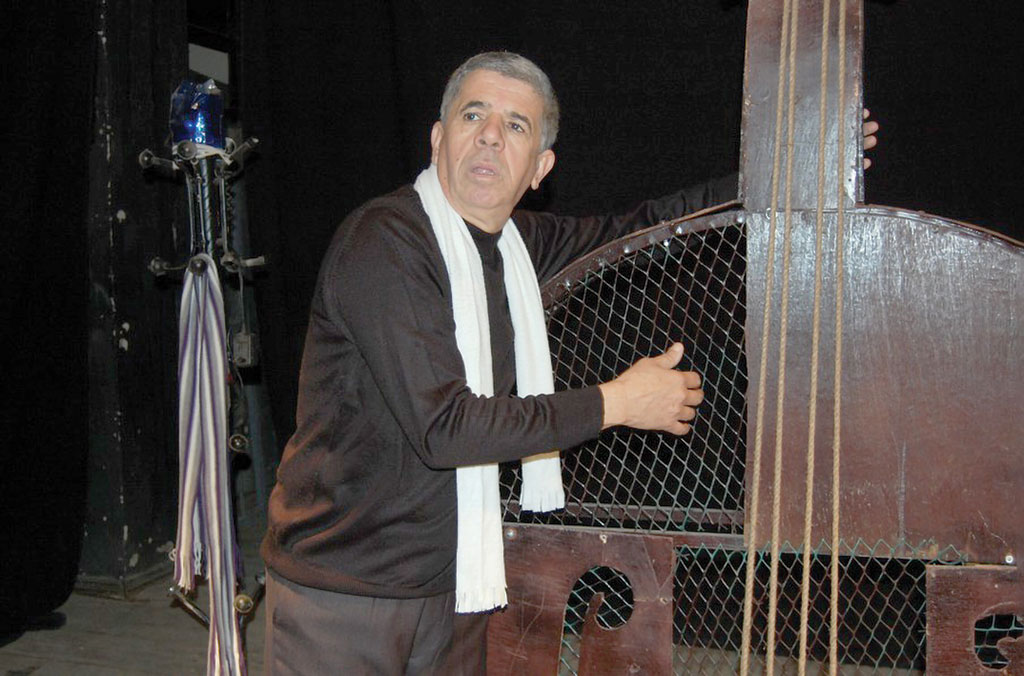

Zs. Sz.: Productions of institutional theatre culture which follow European patterns and reach festivals such as MITEM also model the negotiation process we read about in Eugeno Barba and Savarese’s new book on the concept pair of acculturation and inculturation. According to Barba, the “two complementary dimensions of knowledge” are equally important preconditions for becoming an actor.[25] In the case of Algeria, a young nation-state liberated from colonization in 1962, even the definition of the very place and role of an actor’s existence in the European sense within their society proves necessary. After all, it is an archaic culture rooted in oral traditions, which, at least in terms of the Berber ethnicity living here permanently, may be traced back to the fifth millennium BC. The symbolic hallmark of the performance is a three stringed camel skin-covered bass – this instrument brings such a great success to the musician (played by Azezni Ahchè) who relocated from Algeria to Paris that he will get attention even in his homeland. It is also symbolic that he has to smuggle this double bass home in a coffin, as a result of which he is arrested for blasphemy in violation of Islamic funeral customs after his successful concert. Despite the somewhat complicated storytelling, this production, titled Bravo to the Artist, clearly articulates the fragmented and surreal state of existence which artists attempting to reconcile cultural and civilizational codes must suffer these days.

Á. P.: The talkback after this production also had a surprising account in store: we learnt from playwright Omar Fetmouche how Berber storytellers, who embody a separate social stratum like a caste in the Sahara, in the region of the Tassili Plateau, are telling their stories even today. It is an ancient custom still alive that the audience turn their backs on the storyteller to listen to the stories recited in extremely colourful ways. To them, as we found out, this is the real theatre, because in such a manner the freedom of the audience’s imagination is not limited even by the sight of the performer.

(photo: Zsolt Eöri Szabó, source: nemzetiszinhaz.hu)

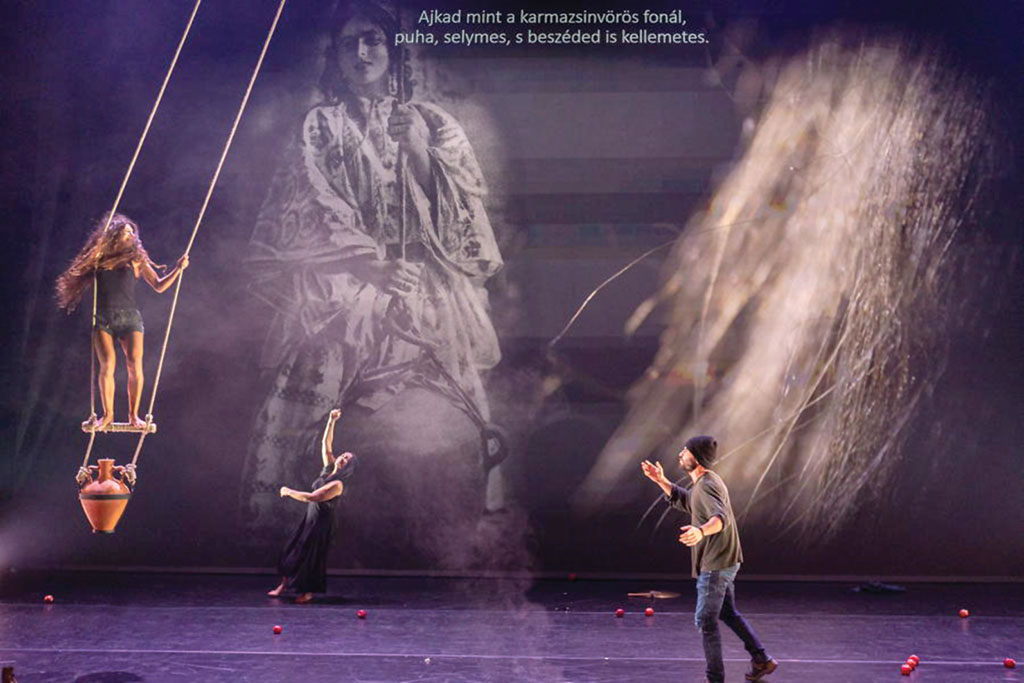

Zs. Sz.: We are finishing our report with El cantar de cantares (Song of Songs), a production by director Ignacio García and the University Museum of Navarre, which, as mentioned also at the talkback, was intended by the creators to be an improvisational and attractive performance adjusted to changing circumstances. The Mediterranean, and Spain within that, has always been a melting pot of cultures distant in space and time. It is natural for the man of today’s globalized world, the consumer of cultural goods, that theatre may also function as a kind of jamsassion, an informal meeting of genres. There is room for projected ethno-photos, with live and moving characters – who all of a sudden leave the acting area and return, while sending us smart phone video messages on the screen – getting copied onto the frames on and off; or for a singer appearing several times with a solo that conveys the emotions of a couple in love. Yet, beyond this overt eclecticism, there is also an unspoken and disturbing question posed by the production, which has come up in this conversation for the second time now: Is it really true that love, the last myth of mankind, stands no chance at all? – Because this couple in the performance apparently surrender to an external force greater than them, when the boy and the girl break apart again and again. – It is worth noting that the director of this production is the apostle of the return to the golden age of 16th century Spanish theatre, and that in this performance the lines of Song of Songs appear in a transcript by Fray Luis de León, a Renaissance theologian-poet. This Old Testament masterpiece of love poetry is remarkable for the fact that love used to be considered part of the mystical experience of God…

Translated by Nóra Durkó

[1] This dialogue began in January 2022, but was completed only in April (– authors)

[2] As a closing event of the Theatre Olympics, a grandiose open-air Tragedy performance is scheduled in Alsó-Sztregova, today Slovenia, with an international staff, directed by Attila Vidnyánszky, who has staged Madách’s work several times during his career.

[3] In Hungarian, see the January, February and March 2022 issues of Szcenárium.

[4] See this work diary here: Visky, András: Mire való a színház? Útban a theatrum theologicum felé, Károli Gáspár Református Egyetem – L’Harmattan Kiadó, Bp., 2020. Excerpts from it were published in the September 2021 issue of Szcenárium pp 26–39, titled Az ember tragédiája mint theatrum theologikum. See the complete work diary here: András Visky: The Tragedy of Man as Theatrum Theologicum (A Dramaturg’s Diary). In: Poetic Rituality in Theatre and Literature, Károli Gáspár University of the Reformed Church in Hungary – L’Harmattan Publishing, Budapest – Paris, 2020, p 225

[5] Pap, Gábor: A Tragédia csillagmítoszi értelmezése a nagy Nap-évben. In: Pap Gábor – Szabó Gyula: Az ember tragédiája a nagy és a kis Nap-évben, Örökség Könyvműhely, Érd, 1999, pp 89–106

[6] In his 1939 production, Antal Németh already made an attempt to direct the chamber theatre version of the Tragedy as a mystery play. György Lengyel praises this performance as a religious ceremony in an intimate atmosphere. See note 9 on page 14 on this in András Visky’s quoted diary: Lengyel, György La tragédie de l’Homme, poème dramatique d’Imre Madách. L’Annuaire théâtral, Numero 47, Printeps 2010, pp 157–171

[7] https://mek.oszk.hu/00800/00876/00876.htm

[8] MAGYARADÁS / Pódium / The Tragedy of Man at the Gergely Csiky State Hungarian Theatre in Timisoara. Released on Youtube: 7 April 2020

[9] Katalin Kemény warns that katastrophe in the Greek language originally meant ‘reversal’, “more precisely the turning point in the drama where the threads of complexity begin to unfold (…).” However, this meaning has been deleted from modern European languages, and it is to be feared that so has the alternative of the conscious dramatic act of ‘reversal’ or active presence with it. Thus, there is a constant danger that “[where] the disturbances and connections of life would be clear, where we could turn to the real and become real, there we crash”. Cp Kemény, Katalin: Az ember, aki ismerte a saját neveit (Széljegyzetek Hamvas Béla Karneváljához). Akadémiai, Bp. 1990, p 41

[10] Examining the nature of the adjective antique, Olga Freidenberg states: we speak of techné when “mythological semantics creates the image of ‘creation’ in the sense of cosmic rebirth and the birth of the cosmos”. Cp.: Olga Frejdenberg: Metafora (ford.: Horváth Márta) = Kultúra, szöveg, narráció. Orosz elméletírók tanulmányai (szerk. Kovács Árpád, V. Gilbert Edit), Pécs, Janus Pannonius Egyetemi Kiadó, 1994, p 244

[11] See: Pálfi Ágnes – Szász Zsolt: Költői és/vagy epikus színház? – Magyar Művészet, 2016/3, pp 61–70

[12] Teodórosz Terzopulosz: Dionüszosz visszatérése. A test (fordította: Regős János), Szcenárium, October 2019, pp 19–27

[13] Theodors Terzopoulos: The Return of Dionysus (with Preface by Erika Fischer-Lichte), Theater der Zeit, 2020

[14] See the bilingual programme guide to MITEM 2020 (ed. Rideg, Zsófia)

[15] Géza Szőcs lived to see the premiere of the play in Szatmárnémeti on October 4 2019. But he died a year later, on November 5 2020, before the premiere in Budapest.

[16] Cf. “Szőcs Gézának valóban volt látnoki képessége” – Sardar Tagirovskyt a Szcenárium szerkesztői kérdezték. Szcenárium, 19 October 2021

[17] Ibid 20

[18] Ibid

[19] Sardar Tagirovsky also qualified as a puppet actor in the studio of the Budapest Puppet Theatre.

[20] Waiting for Godot (in French: En attendant Godot) was first published by Les Éditions de Minuit-in Paris in 1952. Two years later it was published in English by the Grove Press in New York, with significant modifications by the author. The play opened in Paris in 1953 and its English premiere took place in London in 1955. The drama was first published in Hungary in 1965, translated from the French language by Emil Grandpierre Kolozsvári. The translation from the English version by István Pinczés was published in 2010. The play was first staged in Hungary in 1965 and has premiered more than 15 times since.

[21] The prophecies of the Gospels attributed to Jesus, the seemingly contradictory statements, actually stem from the same root: they suggest that we can no longer count with time in the old way. In each case, Jesus speaks of the same paradox of time that characterizes the Age of Aquarius which set in at his birth, approaching it from a different perspective each time. When, quoting from the Psalms of David, he claims that what has already happened is yet to come, he discloses the cyclical operation of world time (the solar year). On the other hand, in the Last Supper scene (Mark 14: 17-32), he makes his disciples aware of personal responsibility, claiming that what is happening in the present is part of the end of times, a prelude to the passion narrative, of which the disciples themselves are thus active participants already; and that his fate is sealed by their betrayal and denial “today, this night”. And his last teaching is that the “day and hour” of the historical geology-scale cosmic drama, the end-time apocalypse is a mystery known only to the Father (Mark 13): But about that day or hour no one knows, not even the angels in heaven, nor the Son, but only the Father. See: Pálfi, Ágnes: A szinoptikusok három világtükre. Márk, az Oroszlán. Szcenárium, September 2015, pp 47–54

[22] Cf. Kultúra, Szöveg, narráció. Orosz elméletírók tanulmányai. In honorem Jurij Lotman (ed. Kovács Árpád, V. Gilbert Edit) Janus Pannonius Egyetemi Kiadó, Pécs, 1994, p 2

[23] Cf. Platón válogatott művei (Selected Works by Plato), Madách Könyvkiadó, Bratislava, 1983, p 158. https://www.goodreads.com/quotes/7302467-and-if-there-were-only-some-way-of-contriving-that

[24] We have made an attempt to rethink this issue in a different context previously. See: Pálfi, Ágnes – Szász, Zsolt: Költői és/vagy epikus színház? Magyar Művészet, 2016/3, pp 61–70

[25] In Hungarian cf. Eugenio Barba: Hogyan válik valaki színésszé? (Part 1, translated by Regős, János), Szcenárium, May 2019, p 42. In English: Eugenio Barba – Nicola Savarese: The Five Continents of Theatre. Facts and Legends about the Material Culture of the Actor. Brill Sece, Leiden – Boston, 2019, pp 160–161

(08 December 2022)