Ágnes Pálfi – Zsolt Szász

It Has Been a Real Inauguration of Theatre!

A Flash Report on MITEM 2016

Zsolt Szász (b. 1959) has been managing editor of the professional journal Szcenárium since its foundation in 2013, and dramaturge at the National Theatre in Budapest (Vitéz lélek /A Knightly Soul/, 2013; János vitéz /John the Valiant/, 2014; Csíksomlyói passió /Passion Play of Csíksomlyó/, 2017). Formerly he directed two productions at the Attila Vidnyánszky-led Csokonai Színház (Csokonai Theatre, Debrecen): Talizmán /Talisman/, 2008; Csongor és Tünde /Csongor and Tünde/, 2010). He was art director of Nyírbátori Szárnyas Sárkány Nemzetközi Utcaszínházi Fesztivál (Winged Dragon Street Theatre Festival in Nyírbátor) from 1993 to 2013. In cooperation with puppet theatre dramaturge Márta Tömöry he created the Nemzetközi Betlehemes Találkozó (International Meeting of Nativity Players) in 1990. He received several national and international awards as an actor, puppeteer and director of the companies established by himself. For his puppeteering activity he was awarded the Blattner Prize in 2007.

Ágnes Pálfi (b. 1952) has been editor of Szcenárium since 2013. Between 1980 and 1993 she edited the Népművelési Intézet (Institute for Culture) journal entitled Kultúra és közösség (Culture and Community) as well as the poetry column of the journal Polísz (Polis) from 1998 to 2005. She had a teaching job first at Toldy Ferenc Gimnázium (Toldy Ferenc Grammar School) from 1994, then, between 1999 and 2009, she was professor at the Department of World Literature, Miskolci Egyetem (University of Miskolc), where she obtained her PhD in 2005. The subjects she taught included the comparative analysis – along the year-cycle model of organic culture – of the grand narratives of the four canonical Gospels and the four modern European “heroes” (Hamlet, Don Juan, Don Quixote, Faust). She has published two collections of essays and five volumes of poetry. A selection of her poetry, Mőbiusz (Mobius), was published in 2014.

Ágnes Pálfi (Á. P.): “It has been a real inauguration of theatre!”, I exclaimed involuntarily when the hour-and-a-half production by Teatro Potlach was over. Well-well, it has taken an Italian company to come along and make us settle in and bless the interior and exterior of our theatre, the building caught in the crossfire of ignoble attacks and debates since its foundation stone was laid. It also makes one think that it was not until this season that the facade has finally received the inscription “Nemzeti Színház” (National Theatre).

Zsolt Szász (Zs. Sz.): Perhaps MITEM itself has not become an event of our own before the third time, either. It has been a special pleasure for me, artistic director of an international street theatre festival[1] over twenty years, to see the appearance of this genre at the event, too. And at such a scale to start with that it could really get the spirit of the place to express itself. It was also justified by the Potlach artists’ accomplishment that the designers of the surroundings of the theatre building and the garden did in those days create a space which, with all its eclecticism, can be operated well and to which symbolic meaning can be attributed.

Á. P.: Some of the stations of that procession evoking the tropes of European culture will certainly be remembered by many. Take for instance the duet of Narcissus and Psyche, the lovers never to meet each other in the interior of the labyrinth, and, along its external curve, the playful evocation of the Fall of Man by means of the apple, which was quasi-offered to the viewers, too, by the hand reaching out of the hedge. The name of Richárd Kránitz’s ship-towing Odysseus in the ten-degree Celsius water of the pool deserves special mention. He, repeating Homer’s text over and over again, inevitably recalled the myth of Sisyphus also.

Zs. Sz.: Let us not forget about the Italian acrobats of the air, either. Because the title metaphor of the production, Angels Over the City, highlights taking possession of that very element as its major stunt (which we, Hungarians may find reminiscent of the visual worlds of László Nagy and Béla Kondor). Ad hoc international collaboration is the order of the day within the realm of street theatre. It was no different in this case, either, with Kaposvár drama students, the Pál family as well as István Berecz taking part in this project besides the Italian troupe of 17 members. It indicates to us that our Italian friends are really sensitive also to where they are invited. And seeing our artists, I believe there is nothing to be ashamed of with respect to current actor training in Hungary. Not to speak of traditional folk culture, which again proved its highest quality during that night. I am convinced that this theatre meeting will be able to turn into a celebration at the same time if it continues to make use of that elementary communication which street theatre alone is capable of.

Á. P.: To my surprise, despite the late hour, quite a few children under ten or so appeared among the audience, apparently having a great time. They must also have felt that those adults had not yet given up hope and trusted that the world was transformable in our image. And that this was just what playing and theatre were for.

Zs. Sz.: Attila Vidnyánszky’s words at the MITEM opening ceremony on the responsibility of artists are still echoing in my ears. I wonder why this concept, smeared in the ’50s and ’60s of the previous century, struck as new several of the renowned foreign directors from Western Europe at the festival. For them, this word is obviously not loaded with that demanding tone in which certain reviewers here got promising artistic careers derailed at the time. Likewise, the festival guests may be unaware of today’s liberal opposition employing the very same word to accuse the leadership of the Nemzeti Színház continuously of lack of social responsibility. At the same time, these experts vindicate their rights as opposition to be the only spokesmen for the so-called oppressed majority of the country.

Á. P.: We had better be keeping our concepts clear. Tadeusz Kantor, called the greatest 20th century theorist-director by Attila Vidnyánszky at the opening of the exhibition dedicated to his memory, provides an example of this clarification of concepts in his writing, published in serial form by Szcenárium last year.[2] In this summary, Kantor, four years prior to the change of regime in Central Europe, while protesting in the name of artistic liberty against artists’ “social motivation” of any kind, analyses the responsibility of theatre in a totally different context:

“The actors want to go on stage from behind the scenes.

NO BACKSTAGE!

NO ’EMERGENCY EXITS’,

NO COMFY NOOKS FOR THEM TO HIDE IN WITH THE DRAMATIC ILLUSION OR THE ROLES OFFERED BY THE AUTHOR.

THERE IS NO ESCAPE FROM THE STAGE.

UNLESS TOWARDS THE AUDIENCE,

INTO REALITY!

THE PRESENCE OF THE ACTOR ON STAGE IS LIKE THAT OF THE CAPTIVE, THE ENTRAPPED,

AS IF HE WAS SURROUNDED BY THE WALLS OF A FORTRESS.

THE SAME IS EXPECTED OF THE SPECTATOR, TOO.

THE SPECTATOR BEARS FULL RESPONSIBILITY FOR COMING TO THE THEATRE.

HE MUST NOT STEP BACK.

THE STAGE AND THE HOUSE ARE ONE!

THE ACTORS AND THE SPECTATORS ARE IN THE SAME BAG.

BOTH PARTIES SHARE EQUAL HAZARDS.”[3]

Zs. Sz.: Similarly to the entire exhibition and the accompanying conference, this writing ought to compel the participants in this general hullabaloo to continue dialogue on these basic questions at a higher level. It was no accident that the idea could be heard at the conference that theatrical life in Hungary would have developed in a different way had Kantor’s oeuvre been integrated into public thought in his own time in the ’70s and ’80s. The characteristically Central-European aesthetic creed of his could have thrown stones into still waters then, which were thus to be stirred only as late as the middle and end of the ’90s by that – originally German – postdramatic theory which has, to this day, been dominating the spirit of theatrological workshops emerging in the meantime.

Á. P.: That is why I was surprised at the receptivity and sustained interest that surrounded the two Polish productions at the “meet the artists” event. Adapted from Ferdydurke by Witold Gombrowicz and Emeryta by Bruno Schulz, Waldemar Smigasiewicz’s direction of Fade-In was easy to digest even without prior knowledge of the two narratives. This performance stages the internal process of aging in a way that – while illustrating the absurd and grotesque end game in the course of which the old man is getting excluded from the external world – it preserves the intimacy and personalness of the internal storytelling all through, by which the director is advocating the value and dignity of human life. I cannot really think of any recent Hungarian productions of this kind.

Radom, d: Waldemar Smigasiewicz (photo: Zsolt Eöri Szabó)

Zs. Sz.: The joint appearance of the child and the old man makes one automatically think of Kantor’s The Dead Class, and even more so on account of those particular school desks, one of which the old man sits into on this stage. However, the performance did not suggest a Kantor-reminiscence. It was the manifestation of the viability of Polish theatrical language created over many generations, which never uses the elements of avant-garde superficially but endeavours to maintain a sense of “shared inspiration” by applying for viewer participation. The road to that leads through the exploration of the personal sphere only.

Á. P.: This “shared inspiration” or inner concentration permeated the stage and the house alike during the production of Acropolys, of which I think it can be genuinely said that it addressed the senses and the spiritual sphere instead of the intellect (that is why it offered an almost complete experience, despite the elimination of subtitling). Through the minimalist stage-setting alone, the director represented a sort of a general, Central-European syndrome: the condition of continuous, unstoppable reconstruction. Human community is present on the stage in the form of a seemingly semiconscious, motor enforcer and it is impossible to say whether he is driven by an external or rather an internal force to take part in this activity. The choir plays the fragments of Vyspiański’s “grand narrative” in an abstract stage space created with an engineer’s exactitude, whether they be stories from the Bible, scenes from Greek mythology or memorable moments in Polish history. This layeredness gradually gives birth to the spiritual dimension which anticipates the coming of the Easter resurrection while keeping both players and viewers in an interim state in contact with life and death. This sublime representation of messianism basically determining Polish mentality is an enviable achievement.

Zs. Sz.: If I understand correctly, you are hinting at a kind of apocalyptic vision of time in the case of Acropolys. I think this is the key to Purcărete’s staging of Gulliver as well. However, while the director of Acropolys, Anna Augustynowicz, represents an utterly transfigured, minimalist approach, the Romanian director exposes bloodied naturalistic visions of existence collapsed into matter. The production noticeably divided audiences but undoubtedly confirmed the aesthete’s lines praising Purcărete’s artistic stance: “With such possible predecessors as Artaud, Grotowski or Kantor, the art of Silviu Purcărete is to be understood simply LITERALLY. Everything is as it seems: plain truth – it is far from making any accusations and it liberates from all predecidedness. It returns the ecstasy of your contradictions, which does not bring fulfillment but makes you free.”[4] Believers in Western Christian eschatology may regard this crude and brutal approach to reality – which does not hesitate to show the procedures of infanticide and cannibalism overtly – as beyond tolerance and the director may even be accused of ungodliness on this basis. However, if we come to think of this sort of cruel theatre from the viewpoint of the iconography in Eastern Orthodoxy, it is worth considering that in it Christ in hell and the related demonology are more extensively treated than in the West and it is closer to the notions of folk belief systems, too. This worldview reckons as equal the negative and positive aspects of the apocalypse, that is, the alternatives of collapse and/or redemption.

Radu Stanca National Theatre,Sibiu, Romania, d: Silviu Purcărete (photo: Zsolt Eöri Szabó)

Á. P.: We hoped that the Belgrade Serbian National Theatre production, The Patriots, would not go completely unnoticed (although tickets were not selling rapidly at first). But for my part, I would not have thought that this premiere would attract so much publicity in Serbia as well as Hungary. You may not agree with me, but I think that András Urbán’s former direction, Neoplanta at the Újvidéki Magyar Színház (Novi Sad Theatre) raised the issue of national identity and the co-existence of different ethnic groups in a more exciting manner. Perhaps it is because the piece was adapted from a Hungarian author’s novel and young Hungarian actors appeared in it, the traumas of the past were also successfully made present. In the case of The Patriots, the caricature-like character of self-criticism, I think, made the performance slightly insipid and at certain points banal.

Zs. Sz.: I agree with you in that Neoplanta was, artistically speaking, a multi-layered and more complex production. Still, I cannot dissociate myself from looking at The Patriots as a military action proper from the perspective of the contemporary evolution of Serbian national self-image. Which proves that art may, even today, have a function of directly shaping society. There is every indication that for Serbs the emotional ventilation of the traumas caused by the lost war in Yugoslavia has gradually become possible due to this very production, too – that is what I was convinced of by the utterances of the company’s leading artists as well as the director of the Serbian theatre at the “meet the artists” event.

Á. P.: At the time we were making the interview with András Urbán in Zenta we did not see the piece, either. Although the director mentioned in advance what forces and emotions had been liberated in the course of staging the production, I was astonished at the extremities characterising this culture so little known to us, and at how the light-hearted enjoyment of life and many times irrational bellicosity, imperial overambition and everyday pettiness can coexist. I must concede that a social satire cannot be expected to soar into metaphysical heights, after all, it is not meant to do that. The manner in which the Serbs present the piece, overtly using the popular tone of folk theatre, also makes a particular audience’s level of energy felt. And this in itself may be instructional to us, Hungarians, living our daily lives on the European scene in the crossfire of artificially induced emotions of hostility.

Zs. Sz.: Force and energy are also a concept pair well worth scrutiny in terms of theatre. I found The Iliad on the second day of the festival the most educational production in this regard. Since the topic of the epic poem, which they call a rhapsody in the old sense of the word, that is a story related by rhapsodos, is fight itself. The pointless fight of forces cancelling each other out, as the director Stathis Livathinos puts it. At the “meet the artists” event, classical philologist György Karsai noted in this respect that because the performance had not shown the duel of Menelaus and Paris, the two symbolic figures of the emotions triggering the war, no drama along the principle of causality developed at the outset, and it was only the compromise made at Hector’s funeral which became the sole drama forming element on stage. Which, we might add, despite all the brilliant technical solutions, made the production energy deficient.

Á. P.: I do not pin this lack of motivation in the dramatic sense on the directorial concept, but ascribe it to the general state of the world to which Livathinos is apparently very sensitive to. Because it is undeniable that – while the reflex to kill is being fed into the three-year-old child’s brain by computer games and all Europe is terrified of the Islamic State terrorists – today we see the almost complete obfuscation of the Venerian motive behind the heroic Martian virtues, which is actually the cause and mover and, if you like, the power base of the war sung in The Iliad. As Plato has Socrates, quoting Diotima, say in The Symposium: the Greek warrior is in effect driven by Venus, the “desire to engender and to bring to birth in the beautiful”. This ancient heritage is a heavy burden today, the director confessed[5], like the stone displayed on the stage, which the Greeks of today as well as perhaps the creator himself would most like to get rid of.

Zs. Sz.: “We are heading for the Sun to kill! Life or death! Üüüü!” Roman general Titus and his victorious warriors enter the stage by that rhythmic ancient Sakha battle cry in TIIT (Titus Andronicus). This very ritual element already carries the peculiar power quality which distinguishes this kind of acting from all the other ensembles’ we have observed at this festival. However, the tremendous success in their case was not only due to the introduction of an exotic culture we had not seen before, but possibly also to their choice of a Shakespeare drama which had never played in Hungary. As director Sergey Potapov said they felt a special affiliation with this early piece of Shakespeare’s, in which the basic motifs of his subsequent dramas already appear.

Á. P.: It is conceivably because Europe in the time of Shakespeare, like now, was going through a crisis of civilisation and culture which was forcing artists to seek the possibilities of revival in reaching back to antiquity. The Renaissance draws, at least in part, upon the “naive” ancient predecessors for a model: for the buoyancy, tradition of form and worldview which give birth to “modern” art. And this ancient antecedent, which in this case is nothing more than a false historical chronicle, certainly bears a strong resemblance to the sakha tradition of olonko, which has been preserved in the sakha’s heroic epics relating their ethnogenesis. And in them, similarly to Greek epic poetry, struggles of tribal type are narrated. However, I think there is another aspect to Asian artists’ zeal for Shakespeare: to them he presumably means the initiating master who discloses the secret of the birth of the modern individual: Hamlet, Lear and Macbeth.

Zs. Sz.: I would not go to lengths to analyse the piece and the performance now (it is actually done by Márta Tömöry in the May 2016 issue). I would like to draw attention to the closing image only: with his depravity magnified to the extreme, Aaron, the villain, crucified on a red cross, stripped of his facial skin, covered in a red cloth, is seen hovering high above the stage, while downstage, surrounded by the corpses, Lucius is sitting, collapsed, with Aaron’s child in his lap. This is radically different from Shakespeare’s work, where the evil, personified by Aaron, is buried under the ground. The loss of face as punishment equals annihilation in the East. However, in this case, it is rather a sort of absolution, a liberation from sins, an act of grace in the Christian sense. It redeems the child, who may thus start life with a clean slate. I believe that with this interpretation of the Shakespeare piece Sakhia and Europe are reconciled at the deepest layers of cult practice. This is an exceptional moment when religious syncretism comes into play.

Á. P.: My first thoughts after the production The Raven by the Alexandrinsky Theatre, Saint Petersburg, were that never before had I experienced such interoperability between radical modernity represented by the avant-garde and the mythical worldview inherited from antiquity. As a former Russianist, I was naturally aware that the other piece by Carlo Gozzi, The Love for Three Oranges, was set to music by Prokofiev on the recommendation of Meyerhold himself and that this opera has been in the standard repertoire of the Russian stage ever since. However, as for the Hungarian theatrical scene, Gozzi is present only through Puccini’s opera, Turandot, and The Stag King on the non-musical front. I think that the opus presented now is not less significant. Nickolay Roshchin’s direction follows truly, scene by scene, Gozzi’s “fiaba”, fairy-play, but its original, period style and the rococo erotism of the love story are radically erased, because on this stage the object of love, the female protagonist remains a dumb captive, a passive puppet all the time. That is why the archaic motifs of the tale may become dominant and be made – by the director – to be seen straight through the existential experience of 21st century man. In this respect, I think it is worth taking a look at the central motif of sacrifice above all. What did it mean in prehistoric times and what does it mean today, for the generations which have experienced the historical turns of fate in the recent past?

Zs. Sz.: The Gozzi play itself is a multi-layered construction as it is. The dramatic story builds upon Jennaro’s excessive self-sacrifice while the bloody chain of events is governed from the background by ruthless fate, over which not even the magician, Norando, quite importantly the father of Armilla, the female protagonist, has power. This fate, commonly called coincidence, is in effect nothing but subjugation to cosmic laws incomprehensible to man. That makes the sacrifice of man, and primarily of woman, inevitable, whichever age they may be living in. An artist of noble descent in the 18th century like Count Gozzi was still manifestly in full possession of the archaic system of images by which the so-called “man of old times” had been trying, and not unsuccessfully, to model these laws.

Á. P.: However, the imagery of the performance shows rather that modern man is the victim of unleashed technical civilisation, at the mercy of the sophisticated and lightning fast automatism of killing. This is demonstrated here by bomb-proof stage technology, almost a self-parody, triggering laughter among the audience again and again – just think of the shooting of the sea monster, the beheading of Armilla’s maid, or Jennaro’s torture, especially the masterfully concocted technology of turning him into a statue, executed to perfection by the machine as a gigantic mechanical puppet much to the spectators’ surprise. Well, well, in what an absurd manner Meyerhold’s demand was met for the immediate introduction of cutting edge industrial technologies into the theatre![6]

Zs. Sz.: A possible reading of it is that machine, taking over the governing function of destiny, has subdued man for good. Still, it is not only machine ruling over him: there is a view-tower-like construction looming over the acting area throughout the performance, seating the orchestra, with Norando, the magician in charge as conductor. However, the gestures of the aging actor with an excellent tone of voice remind one much more of the omnipotent leaders of the former Soviet empire than the wizard of fairy tales or the practising artist. It is because of the permanent presence of this “superhuman man” that one feels at the end of the play that nothing has changed in fact: the acting area for us remains restricted to as much as this authoritarian power, which has survived itself, allows.

Á. P.: Norando raises her daughter from the dead as if he was only snatching up a puppet from the ground. And there is no happy ending, no lovers finding each other. Yet, the production had one cathartic moment: the resurrection of Jennaro cast into concrete – as if the fallible, beautiful man’s body had spun out of a rock-hard womb to be born again. Under the influence of this image, the spectator tends to forget that the price of this revival has been the brutal slaying of Armilla (and not her voluntary sacrifice, like in the original fairy tale).

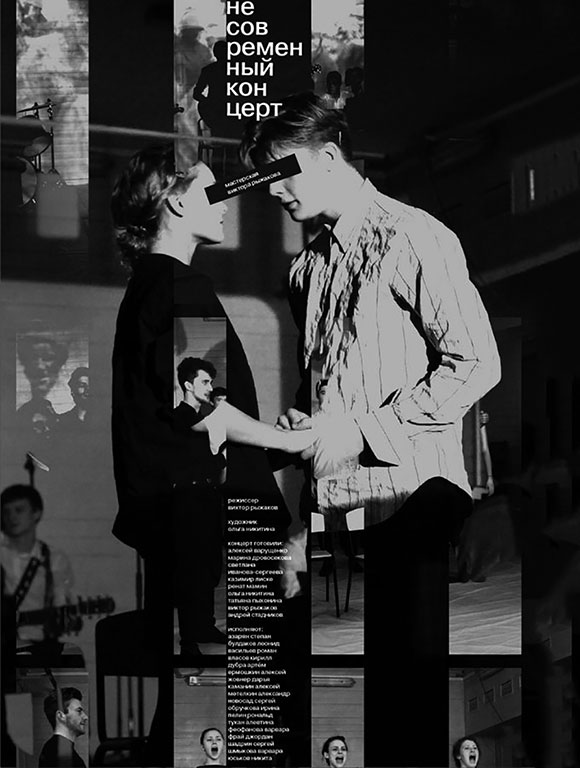

Zs. Sz.: Although it carries a different weight, Victor Ryzhakov’s direction of Anachronistic Concert, presented by the Moscow Art Theatre School, may be worth mentioning at this point. Above all because its topic is the very same recent past as underlying in the frame story of The Raven: the question is the attitude of today’s Russian society to Soviet times. If we perceive Ryzhakov’s direction as a work of art in its own right under his name, we will, let us face it, be in for a sense of lack. Especially if we come to think of Gogolrevizor two years ago, an object lesson in the application of instruments which may make classics our contemporaries.[7] However, if the production is regarded merely as an exam performance in which undergraduates had a chance to try the techniques of verbatim theatre, we can say we have seen a loose string of cabaret scenes based on clever character-acting, accomplished brilliantly by the students – solo or duet – in possession of Stanislavsky’s method.

Á. P.: The enthralling vocal, instrumental and dancing skills of the undergraduates testify to the invariably high standard of Russian actor training. But if we take that the students theatralised interviews with members of the war-stricken great-grandparents’ generation, we face the paradox of verbatim theatre. Since the humour in this stage play was, I think, much more demonstrative of the generation gap than of the social sensitivity which the believers of this school wish to aim at. It was only at the “meet the artists” event that we became convinced that children were genuinely shocked by these “spontaneous” encounters.

Zs. Sz.: Similarly to Ryzhakov’s production, Psyche, an adaptation of Sándor Weöres’s masterpiece, is a workshop production, the final exam performance of Attila Vidnyánszky’s third-year students. Probably it is no exaggeration to say that this production made Weöres a classic playwright. Which means, at the same time, that theatrical language in Hungary became suitable as late as forty plus years after the publication of the book to prove – for the second time following Gábor Bódy’s film – that provided there is a valid Hungarian postmodernism, this is really one such work and as imperishable as the 19th century classics.

Á. P.: Bódy’s film is now at the cutting edge of the world’s film history due in no small measure to the splendid selection of the two protagonists, Patricia Adriani and Udo Kier, who – according, among others, to György Cserhalmi who also acts in the film – do not represent such a quality in acting as do their Hungarian colleagues in the film. I pondered a lot on why Bódy had still chosen them. I concluded that it was exactly because of their foreignness and intangibility: they are like the heroes of a fairy tale for adults, existing not in ordinary reality.

Zs. Sz.: At the “meet the artists” event, Attila Vidnyánszky confessed to having searched for the actress to embody Psyche since 1989. Finally, in the course of this one-year workshop activity, he decided to cast seven persons in this role, that is all the girls in his class. Not only has this solution opened the door to presenting the postmodern concept of “split personality” on stage, but has also made the students complete the school of initiation to become an actress, in the course of which the narcissistic self-image, the greatest hindrance to ripening in this profession, needs to be destroyed. (Let us remember Péter Popper’s popular book, Színes pokol (Coloured Hell) on this problem.) The director’s inventiveness liberates, and not for a moment in a naturalistic manner, that natural eroticism on the stage which is peculiar to this Weöres piece.

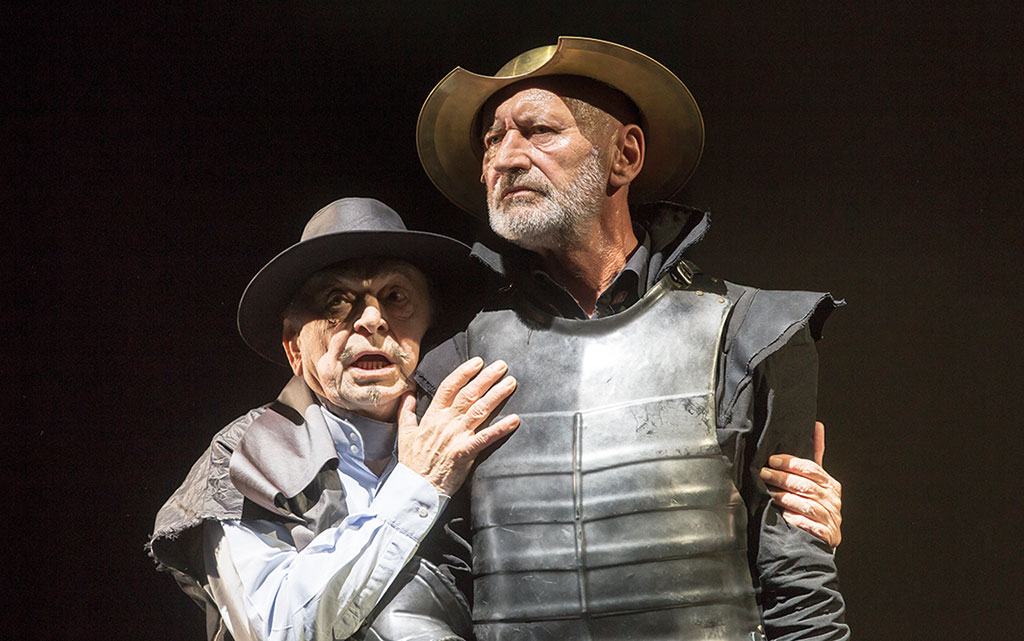

Á. P.: We have got used to seeing a growing number of epic works on European and Hungarian stages since the 1980s. Even Dostoevsky, the greatest novelist in the 19th century, was already preoccupied with the question of the interoperability of major forms/genres. His admonition for instance that no novel should be dramatized on stage in full provides us with food for thought.[8] Scanning through the Nemzeti Színház productions at MITEM III, we will see that all but one of them have a novel or a short story as their raw material (Weöres’s above mentioned Psyche includes – apart from Erzsébet Lónyai, the imaginary heroine’s poems and works by László Tóth, a real-life poet – a fictitious autobiographical diary, prosaic reminiscences as well as contemporary documents; Don Quixote, staged by Attila Vidnyánszky, was adapted by Ernő Verebes from Cervantes’ novel; Sardar Tagirovsky directed the production based on Chekhov’s short story, Ward 6; Péter Galambos, director of Szeszélyes nyár (Summer of Caprice), drew upon and continued to write Vladislav Vancura’s novel of the same title).

National Theatre, Budapest, d: Péter Galambos (photo: Zsolt Eöri Szabó)

Zs. Sz.: Galilei élete (The Life of Galilei), staged by Sándor Zsótér, also represented the so-called “epic drama”. This term, as we know, refers to the 20th century turn in theatre history, associated with Bertold Brecht, which may as well be regarded as the preliminary to the postdramatic school, unfolding towards the end of the century. A cornerstone of this concept is that dramatic dialogue in the classical sense is no longer thinkable on stage today. In our discussion apropos of Don Quixote, we dealt with the problem of dramatization from this aspect, too, and also with along what strategy cooperation had been realized between Ernő Verebes, who adapted the novel into a dramatic piece in its own right, and director Attila Vidnyánszky.[9] This issue is treated by writings published on the other productions, too.

Á. P.: The epic tendencies in theatre may stem from that changed condition of the world that the participants in dramatic events with global implications do not act in a shared space-time continuum, that is, in many cases, they do not even meet each other in physical space. In the virtual world of the film it does not pose a problem so to say because the function of the “superhero” is precisely to connect the distant points and characters in space-time. However, these “superheroes” today increasingly tend to be creatures without a personality, the humanoid operators of robotics only. The hardest task for theatre in this situation is to build a character, since the director is working with flesh-and-blood persons, with actors of their own individuality. It can equally be said of the productions mentioned above that in them these particular segments of space-time enter into a dialogic relationship, normally with a transmission similar to the authorial (or formal) narration in a novel. The characters’ dialogues fulfill their own dramatic and/or epic function only in the resulting dialogic space, which makes it difficult but not impossible for them in certain moments to, so to say, get right inside their part offered by the situation. In my opinion, this kind of major form/genre approach offers a nuanced system of criteria which could give way to explaining what the Nemzeti Színház represents across the Hungarian theatrical spectrum today.

Budapest, d: Sándor Zsótér (photo: Zsolt Eöri Szabó)

Zs. Sz.: By contrast, there were three dramas featuring at MITEM where it was hard to decide why the directors deconstructed the original dramatic conflict: was it due to the changed condition of the world, or rather just yielding to the “new” instruments’ pressure of form created in the wake of the postdramatic idea? At the beginning of The Seagull, directed by Thomas Ostermeier, Matthieu Sampeur in the role of Treplyov does in fact itemise today’s “compulsory” clichés: have the actors frontally seated in a single line, facing the spectators, and so recite long texts; use handheld or stand microphones to crank up internal speech; use a megaphone if you want to talk aside; get naked if you mean to be frank; and let a lot of fake blood flow on the stage… Besides, interacting with the audience is compulsory (in the case of The Seagull it took the shape of a current political foreplay, which I think was meant to be ironic about the obligatory style seen in today’s theatre and provoke the hosts at the same time). Compared to that, acting seemed rather conservative: the company used the instruments of psycho-realism based on Stanislavsky’s method.

Á. P.: Even last year, watching the Burgtheater production, I very seriously asked the question whether Chekhov’s dramas were so topical as need to be put on stage year after year. As far as The Seagull is concerned, I can detect the flaw with artist dynasties much rather in that parents want stardom for their children too soon, and not in wanting to delay their career success, as shown in this production.

Zs. Sz.: A similar thought came to me watching Shakespeare’s last comedy, Twelfth Night, or What You Will, directed by László Bocsárdi. In this play Shakespeare himself applied merely the top-flight comedy technique he had developed, where cross-gender casting could no longer contribute anything really new. In the original play the only novelty is the appearance of and teaching a lesson to the Puritan Malvolio, which is an anticipation of Molière. However, this role here – even though played by Tibor Pálffy, who was admired in The Miser last year – was going to be simply one among the many caricature-like, overillustrated characters.

between Áron Tamási Theatre (Romania) and Gyula Castle Theatre (Hungary),

d: László Bocsárdi (photo: Zsolt Eöri Szabó)

Á. P.: If there are two diametrically opposed directorial concepts, the interpretations of The Lower Depths last and this year might well be called so – the former is a tribute to Victor Ryzhakov, the latter to David Doiashvili. On Ryzhakov’s stage, the man of today appears in Act two as someone beyond good and evil, to use Nietzsche’s famed term, lying on the deckchair turning in on himself – though in the company of others –, as if he was offering his body to the beams of the sun in order to recover from his troubled past, trusting only in the redeeming power of recreation. Doiashvili’s reading represents just the opposite extreme: as though the fierce battle between good and evil in the human soul would never come to an end, and we were condemned to never find our peace of mind, even after death.

Zs. Sz.: I had similar feelings about the production. However, it seemed as if the play itself was merely an excuse to Doiashvili for drumming his conviction in its physical concreteness into us that we cannot or probably do not want to break free from the captivity of the struggle between good and evil. That is why the role of Luka, the wandering philosopher, becomes weightless on this stage. As a consequence, the production finds itself outside the horizon of interpretation offered by the Gorky piece, which phenomenon is surely not unique in today’s theatrical directorial practice – and may even turn out a success, like in the case of the above mentioned Gogolrevizor. Still, in that case, I would question whether this Gorky play is really suitable for Doiashvili to present his obsession in its entirety, with all its layers.

Á. P.: The frame of Federico Garcia Lorca’s play, The Audience, is similar to the prelude in Goethe’s Faust, where the poet, the clown and the director discuss what contemporary theatre ought to be like and what the audience wanted. The low-lit stage set, against the backdrop of the silvery vibrant strip curtains, evokes the profane world of cabarets and the ethereal, surreal abstractions of poetry simultaneously. However, in the foreground there is the sand, the earth, which is the instantiation of physical concreteness, just like the naked bodies are there not only to indirectly refer to “otherness”, but also to make the elementary attraction and repulsion of sexuality felt in its primary form and induce it in the audience, too.

Zs. Sz.: The question may arise whether the real intention of director Alex Rigola with this production was to test and demonstrate the effect on the audience of the theatricality of sexuality. Or, rather, to bring over and shoulder in full Lorca’s attempt to create surrealist drama, also as something which may serve as a model for a possible contemporary theatrical discourse. I am saying all this because in the structure of the play the topoi of the two previous great eras of the history of drama, the ancient Greek and the Spanish Golden Age (for example the sun’s horses, the infante), carry at least the same weight as the dramatic cases in Freud’s depth psychology (sibling love, homosexuality, the Oedipus complex). I admit these are no petty points. However, they did not fall into place to provide a holistic experience to me like the contemporary Buñuel’s film, An Andalusian Dog, which overwhelms one time and again.

Á. P.: It reminds me of the paragraph in Kantor’s above-mentioned text, in which he says that for his part he no longer really believes in the “power of dream-like vision” cultivated by the surrealists, which, so to speak, “brings imagination to life”. He thinks that the “freedom of ideas and associations” is not created by vision, but “by the intensity of meditative activity”. This enables one to disengage from “rational relations, the utilitarian association of realistic elements”. The emphasis on the “primacy of liberated thought”[10] I think is very timely now that we live in an age when there is a profusion of images and visual effects. Maybe that is why none of us are really impressed by the kind of surreal vision which in this production – at least according to the director’s interpretation and commentary – characterises Lorca, one of the most outstanding representatives of the trend.

Zs. Sz.: The production The Breeding Pool of Names by Valère Novarina both as author and director closes on a philosophical aside, a miniature epilogue if you like, that this scenario will never come to an end because there is always a next line. This enigmatic utterance, like the title of the production, concretely indicates that we see a word theatre here. A production, which is based on the author’s philosophy of language attitude focussing on the world of theatre. It is in many respects an abstract but still continuous reflection grounded on artistic practice, the central idea of which is that word cannot possibly be non-situated on stage. As Novarina puts it in a TV interview during MITEM: “the stage is a living laboratory of language”[11]. So it is a playing space which operates and transforms things, language included, into real with – as a result of its artificiality – higher efficiency than it is experienced in everyday life. However, it is a question whether this transformation has taken place in this case or not.

partners: Festival d’Avignon / CDN de Montluçon, Le Fracas, d: Valère Novarina (photo: Zsolt Eöri Szabó)

Á. P.: Based on the premiere in Debrecen of Imaginary Operetta, we had every reason to hope that we were then witnessing a similar success, but, unfortunately, it did not turn out to be the case. I wonder why. If one comes to think of it, the creation and reception of the production were greatly eased in the case of the Imaginary Operetta by the fact that operetta is a national genre in Hungary. The cabaret has a long tradition also, so it is not surprising that Queneau’s neoavantgarde piece, Exercises in Style, was bringing down the house for decades. However, this variant of the avant-garde represented by Novarina, which is reminiscent of the Dadaists’ artistic process primarily, is less cultivated here, though not unknown.

Zs. Sz.: I have the impression that Novarina’s popularisers in Hungary prefer the “elevation” of this philosophy of art, and do not so much stress that Novarina is actually a “comedian making a cruel theatre”, as he himself underlined it in the above-quoted interview. Nevertheless, we can be grateful to them, especially to Zsófia Rideg, who has been engaged in the “naturalization” of this oeuvre for more than a decade. Novarina was deservedly the guest of honour at MITEM III, by two theatrical performances and a professional discussion as well as a musical reading recital.

Á. P.: It is also owing to the mediatory role of Zsófia Rideg and Arwad Esber, the director of the Festival de l’Imaginaire, that we could see the Korean Jindo island shamanic funeral ritual. For me it was real theatre, probably because I was not in the first place socialised in stone theatres: Péter Halász’s room theatre was not one, and nor were the productions of the Living or the Street Theatre Festival, Nyírbátor, or the IDMC workshops. Therefore I did not quite understand why the Hungarian audience became so divided over this performance.

Zs. Sz.: We must concede that it was no theatre for the Pest public, reared on bourgeois theatre. I think it proved once again that such events ought to be prepared in a different way. In addition to the specialized articles we published in Szcenárium[12] on this ritual as well as Korean theatre, a different kind of intro and publicity would have been necessary so as not to have to raise awareness directly before the production, right on the stage, in two languages, and at great length. I also badly missed the usual “meet the artist” event where I as a moderator could have drawn attention to a parallel or two with rites in traditional Hungarian folk culture, such as the conceptual similarity which is discernible between Korean funerary rites and Hungarian wedding rituals. The Koreans’ symbolic coffin of the dead betrays in almost every element the same construction as the symbolic object used at weddings in the village Boldog, Heves county: the ’menyasszonykalács’[13] (’bridal cake’), with the function of rendering the wedding ceremony as a ritual to bury maidenhood. This rite was celebrated here even not so long ago by women, in the same way as the Korean funeral ceremony is performed by women to this very day.

Á. P.: The Hungarian public still seems somewhat aloof from traditional Chinese opera. As far as I know, tickets even to the world-renowned Beijing Opera’s production were not easy to sell at POSzT (Pécs National Theatre Festival) two years ago. So the great success of the Sichuan opera (Chongqing Sichuan Opera Theatre) may as well be considered a breakthrough – which may primarily be due to the fact that this kind of Chinese opera is reminiscent of 19th-century romantic and verist Italian opera. But the success is also attributed to the fact that the company is led by an artist like Shen Tiemei, who, in addition to being a “living national treasure”, is an excellent communicator. He proved this after the production when he addressed the audience from the stage “as a civilian” already, and did even more so at the workshop where, following a demonstration, he brought the public close to understanding what makes Chinese theatre culture so unique and viable: he talked in the most natural way of the day by day sacrifices taken not to let the smallest element of the centuries-old tradition waste away.

(photo: Zsolt Eöri Szabó)

Zs. Sz.: Hungarian recipients badly need workshops like that, which amount to an initiation. The most important lesson I have learnt from this one is that artists in the East, even to this day, base themselves in every respect on techne, which is by no means the same as what we in the West mean by the technical skills of the artist.[14] We came to know that they spend at least three hours preparing before stepping onto stage. We were shown how for example the headwear characterising a figure was being made, and meanwhile we also found out why those countless props – like ribbons, beads, hairnets, wigs, human and animal hair –, which seem so superfluous to European eyes, were necessary to make the very appearance of the figure carry the same complexity as conveyed by the broad spectrum of its gestures and voice during the performance. This complicated sequence of operations also substantiated strongly that Eastern high cultures have preserved their faith in the magical power of hair to this day. Just as they also consider very important that which is out of the sight of the audience, but which – like a secret gene that enables you to become initiated – every one of us in fact is bearing inside, both in the East and the West.

[1] See Szász, Zs.: ’Genius Loci’, Szcenárium, April 2014, pp 27–33

[2] Kantor, T.: ‘A színház elemi iskolája’ (translated into Hungarian by Katona, I.). See chapters in Szcenárium December 2014, January to May 2015

[3] Cf. op. cit. Part 3 in Szcenárium, February 2015, pp 16–7

[4] Cf. Popa, S.-V.: ’A dráma celebrálása’ (translated into Hungarian by Kulcsár, E.), Szcenárium, February 2014, pp 5–6

[5] Livathinos spoke of the burden the ancient Greeks represent at the roundtable discussion ’National Theatres in the 21st Century’ at MITEM III on 13 April.

[6] See the study by Picon-Vallin, B. on Meyerhold, translated into Hungarian by Pálfi, Á. in Szcenárium, September 2015, pp 23–35

[7] See Pálfi, Á., Szász, Zs.: ’Önazonosság és művészlét’, Szcenárium, April 2014, pp 17–18

[8] See Király, Gy.: Dosztojevszkij és az orosz próza (Akadémiai Kiadó, 1983), pp 318–343

[9] See ’A hősi hóbort ragálya’ (A roundtable discussion with Tömöry, M., Szász, Zs. and Pálfi, Á. on the premiere of Don Quixote at the Nemzeti Színház), Szcenárium, October 2015, pp 62–70

[10] Cf. op. cit. P 34

[11] Cf. Éva Andor’s interview with the author, Faktor television, 16 March 2016

[12] Birtalan, Á.: ’Oldás és kötés’, Szcenárium, February 2016, pp 16–24; Tömöry, M.: ’A koreai népi színjátszó hagyományról’, Szcenárium, December 2015, pp 5–14

[13] Both have the designation of the four corners of the world, the three phases of the sun, the dead body with the germs of life sprouting forth, and the rooster as a symbol of death and resurrection.

[14] Techne is defined as when mythological semantics generate the image of ’creation’ in terms of cosmic rebirth and the birth of the cosmos; see Freydenberg, O.: ’Metafora’ in Hungarian, in Kovács, Á., V. Gilbert, E. (Ed.): Kultúra, szöveg, narráció (Janus Pannonius Egyetemi Kiadó, Pécs, 1994), p 244

(09 December 2022)