Ágnes Pálfi: The Pregnancy of Feminine Vigilance in The Tragedy of Man

A Reading of the Eskimo Scene

According to the “astro-mythological” interpretation by Gábor Pap, Az ember tragédiája (The Tragedy of Man) by Madách reaches its nadir in the axial Paris scene (Scene 9), the apocalyptic judgement situation of the Libra decan of Aquarius, which, however, does not appear on the everyday level but as a vision, as a dream within a dream.[1] He describes the successive order of the scenes in The Tragedy so: “The first scene is the heavenly one, the level of the Father. The next one is Eden or Paradise, the level of the created world which is still sinless. The third is the scene outside Paradise, the level of the fallen world. It is at the end of this one that the couple falls asleep and the dream or historical scenes begin. Among the latter ones, the middle three scenes have relative autonomy and the Paris one drops to a lower level again, because it is a dream within the dream: dreamt by Adam as Kepler in Prague. In the last one, Scene 15, we return to the level of Scene 3, outside Paradise, but we will not rise higher than that.”[2]

Yet, if we ask which the two correspondable scenes that bring us face to face with the end as concrete corporeal reality are, the answer is clear: they are the London scene (Scene 11), which is the last act in history, and the Eskimo scene (Scene 14, the World of Ice), which is the end game of life on earth. Still, this naturalistically concrete end game does not lead to destruction with Madách.

It is worth quoting the author’s instruction word for word because it reveals that he was not thinking of an ordinary change of sets to follow the Eskimo scene, but pictured a real metamorphosis to himself[3]: (“The scene changes back to the set of Scene III. A landscape with palm trees. Adam, as a young man again, is seen leaving the hut, heavy with sleep. He looks around him in amazement. Eve is still asleep inside. Lucifer is standing in the middle of the stage. Bright sunshine.”) (SCENE XV) Therefore, the area of the Eskimo scene, the “Barren, mountainous landscape, covered in snow and ice”, changes to a landscape with palm trees in front of the viewer’s eyes. And surely it is no coincidence either that the abode of the first couple is called a “hut” here by Madách, just like in the Eskimo scene previously. However, Scene 3 originally had “a rough wooden shack” instead of the “hut”. This may give rise to the assumption that it is still the Eskimo woman having fallen asleep during the former scene who is now talking as Eve, to wake up soon and step out into the light with a new look already:

“Adam, why did you steal away from me?

You seemed remote. Your kisses made me shiver.

I read despair or anger in your face.…”

(SCENE XV)

By no means is it certain then that Eve has woken up from the very same dream as being choreographed by Lucifer. Because the utterance she has just made suggests she does not remember a thing of all that she was supposed to be watching together with Adam. She appears to have been untouched by the historical scenes. And, apparently, she does not suspect that Adam is going to make a fatal move: to commit suicide.

Though in the garden of Eden, she was original sin. She was the one to take an apple from the forbidden tree. She was female hubris, rebelling against her “cruel” creator and wishing to know all secrets, obsessed with curiosity. She did not shrink from Lucifer’s offer or fear the wrath of the Lord. She was the “first philosopher”, she was basic trust in the divine plan:

“Why should He punish us? If He appointed

a path upon which we were meant to walk,

most likely He would have us so created

that no enticement could prompt us to leave it.

Or would He have us perched above the gulf

without a head for height and doomed to fall?

But if our trespass were of His designing,

like storms which rumble in the sunny season,

then who could allocate the rights and wrongs

between the days of thunder and of heat?”

(SCENE II)

Having tasted the apple, Adam will submit to this overwhelming female force first, and hear Lucifer’s offer only later and decide to embark on the great adventure now really manfully:

“… to see the future

my strife and suffering will bring to pass.”

(SCENE III)

Strife? Suffering? – the female ear seems to be deaf to these words. The prophetic dream, the “charm” that Lucifer puts on them means something utterly different (what a cheeky play on words by Madách!) to Eve: her own charm, her looks.

“I’d love to see these changes working through:

if I shall always look – the way I do.”

(SCENE III)

Never does Lucifer, the pedant dramaturge, forget about this vain womanly question throughout the historical scenes. And his response is positive time and time again: womankind has nothing to worry about in this respect. Eve will stay as attractive as ever, passing time will spare her, and no matter she changes roles and costumes, Adam will see her in all “these changes working through”. Although he is far from always feeling the same flame of love for her. He gets disappointed with her several times and, in two cases, he seems to be turning away from her for good. In the Paris scene he is appalled at the wanton “tigress” of the popular uprising who passionately kills a man and wants to be rewarded for her bloody act – only asking, or rather demanding the “great man”, Adam-Danton, to “spend the night” with her. And in the last scene before the awakening Adam recoils from the sex offered, presumably also because of female violence. Or does he not? Could Eskimo Eve’s animal magnetism still have overcome disgust in Adam?

“The animal within you claims the first place” (SCENE XIV) – says Lucifer to Adam beforehand, meaning this very scene to be the last “lesson, /another chance to get to know yourself”. However, Adam, this “broken, old man”, is believed to be a real god by the Eskimo man who not only sacrifices the first seal to him but also offers him his woman. True, the custom of “guest rights” itself also dictates so; but, behind the profane surface, the sacred background to this gesture emerges as well. The Eskimo may well hold the view that this sexual act is the ritual of unification with the “old god”, the life-renewing “sacred union” – or as Pilinszky (TN: Hungarian poet, 1921–1981) would say: “the celebration of nadir”. From this point of view, the question may rightly be asked: does not the miraculous transformation of the scene at the beginning of Scene 15 suggest that Adam has eventually been able to consummate as well as consecrate the union – which, as Miklós Hubay says in his book[4], has been delayed up until now – to Eskimo Eve right at this nadir? And is the Lord not speaking again for the same reason, practicing the so-called “free grace” – without finally destroying humanity?[5]

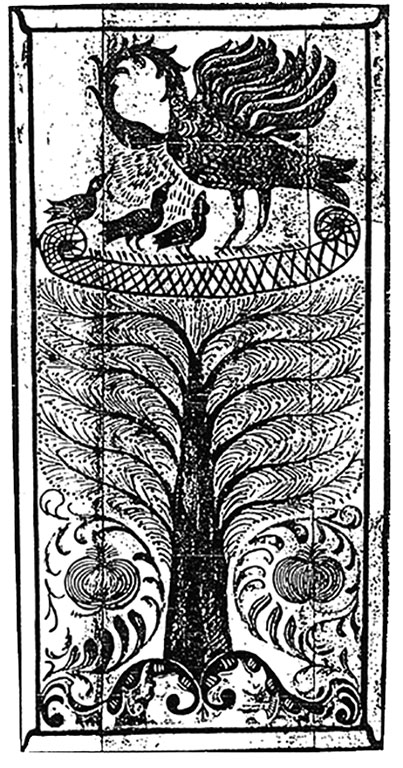

Scene 14 (The World of Ice), paper, carbon, 790×503 mm, 1887 (source: mng.hu)

No matter how this sequence of scenes is interpreted, it is indisputable that Madách’s text is ambiguous at this point. That is, the author does not give any indication as to what Adam and Eskimo Eve are doing or not doing and how much time they actually spend together in this particular “hut” – is it only a moment, an hour or a full night?

“MAN

[entering the hut]

Wife! Visitors!

Now, see to it, and make them comfortable.

Eve throws her arms round Adam’s neck and tries to drag him into the hut. Adam is struggling to shake her off.

EVE

Welcome, stranger! Come, make yourself at home!

ADAM

Help! Help! Lucifer! Get me out of here!

Back to the present time. Confound the future!

I’ve had enough of sights, this pointless struggle

with destiny. It’s time to think again:

dare I wage war against the will of God!?”

(SCENE XIV)

It can be reasonably assumed that Madách made a conscious decision at this delicate point to leave it to the discretion, to the taste, temperament and mindset of prospective stage directors to abandon or present the very act. Just as the question is also well-founded as to what is conveyed – beyond the back reference to the Eskimo scene – by the fact that instead of mentioning the negative experience of historical scenes, Eve, awakening from her sleep, asks for the cause of Adam’s estrangement. Is it because she is only interested in herself, in the soap opera of her indestructible charm? Or is she motivated by a deeper insight?

In my reading, Eve was not having the same dream as Adam. This I think is already made obvious by Madách through the fact that Eve is never present as a third party in the company of Adam and Lucifer when, having left a previous scene, they are heading towards the subsequent station.[6] Eve is elsewhere, or to take a different approach, she is just as invisibly present in the moment of scene changes as the Lord. While walking through the stages of the story of mankind, Eve cherishes one image in herself: the changing forms and facial features of Adam.

In The Tragedy, Eve’s dream is the secret story of the conception of the new Adam. And it is the secret story of maturing into motherhood, of which there is hardly any information even in the most prominent works of literature. That is what makes the narrative about Psyche so precious in Apuleus’ novel[7]: it is the “earthly Venus’” story of feminine initiation, which has the mystical union with Eros as its turning point, and which is followed by the just punishment for her curiosity, Psyche’s exile. These stages from conception to childbirth ripen her into a mother until she finally acquires Zeus’ grace and her deserved rank in the heavenly and earthly hierarchy.

There is a passage in Plato’s Symposium where Socrates argues that pregnancy precedes conception. Here the philosopher is not arguing in his own name any longer; Diotima, the priestess, is quoted as a credible source, and she is made to say the final word to settle the men’s dispute on the nature of Eros:

“…when approaching beauty, the conceiving power is propitious, and diffusive, and benign, and begets and bears fruit: at the sight of ugliness she frowns and contracts and has a sense of pain, and turns away, and shrivels up, and not without a pang refrains from conception. And this is the reason why, when the hour of conception arrives, and the teeming nature is full, there is such a flutter and ecstasy about beauty whose approach is the alleviation of the pain of travail. For love, Socrates, is not, as you imagine, the love of the beautiful only.” “What then?” “The love of generation and of birth in beauty.”[8]

I wonder how this fertility, conception following pregnancy, is to be interpreted in the case of Madách’s Eve. – I imagine that in her dream, Eve is rather active: she is contemplating the man’s passion story, his pupal states throughout history, and carries it all as spiritual existential eperience through the filter of the psyche into living biological matter. To use a trendy technical term, she is “encoding” into the unborn one what its job is going to be. It is possible to mass produce cannon fodders, standardised people in a different way, whether in a test tube or by cloning. But the genetic programme of this artificially produced creature will be lacking in the spiritual surplus of Eve’s dream.

This pregnancy of feminine vigilance – in which spirit, mind and body are active as one – is painfully absent from Goethe’s Helena as well. She and Faust are twin-like creatures reflected in each other’s dream: the sculptures of perfect beauty. The child of their “aesthetic” union, Euphorion, is an ecstatic artist; his disembodied spirit rises to the sky, having no more earthly mission.

In The Tragedy, however, Eve’s dream is constant feminine vigilance itself. A ready-to-conceive, fertile pregnancy. I imagine her as the female figure on the famous Scythian belt buckle, a prehistoric woman sprouting a tendril from her hair, sitting with her back straight at the foot of the world tree.

She is keeping a vigil, hiding the feverish man’s head into her lap and looking inside it with her spiritual eyes; she is not gazing at Lucifer’s comedy. She is seeing another Egypt, another Byzantium, Athens, Rome, Paris and London – and, listening to the heartbeat of the fruit of her womb, another Budapest.

English translation by

Mrs. Durkó, Nóra Varga

Published in Hungarian:

Szcenárium, September 2013

[1] This is an extract from the following extensive study: Ágnes Pálfi ’A női éberség másállapota’. (’The Pregnancy of Female Awareness. On the Figure of Éva in Az ember tragédiája (The Tragedy of Man) Apropos of Miklós Hubay’s Book on Madách’), Szcenárium, September 2013, pp. 29–41

[2] Cf. Pap, Gábor – Szabó, Gyula: Az ember tragédiája a nagy és a kis Nap-évben. (The Tragedy of Man in the Large and Small Solar Cycles) Örökség Könyvműhely, Érd, 1999, pp. 97–98

[3] In The Tragedy, the only similar instruction by the dramatist comes at the other prominent point of the dream dramaturgy, at the beginning of the Paris scene. The metamorphosis of objects in the preceding Prague scene is quite surreal in this description: “The scene suddenly changes to La Place de Grève. The balcony turns into a scaffold, and the desk into a guillotine…” (SCENE IX) (The quotes from Madách’s work are taken from the English translation and adaptation by Iain Macleod, Imre Madách: The Tragedy of Man, Canongate Press, Edinburgh, 1993 in: http://mek.oszk.hu/00900/00917/html/ with the no. of scenes indicated in brackets.)

[4] Hubay Miklós: “Aztán mivégre az egész teremtés?” Jegyzetek az Úr és Madách Imre műveinek margójára. (“And as for This Creation – What’s the Purpose?” Notes on the Margin of the Works of the Lord and Imre Madách) Napkút Kiadó, Budapest, 2010

[5] According to the interpretation of Gábor Pap, the human couple’s waking is to be located in the spacetime of Sagittarius, where the positive turn is the result of the outflow of beneficial fatherly energies (see op. cit. pp. 133–134). If that is true, then the reviving first parents are to find shape in Gemini opposite Sagittarius. And this may mean that they are to unite in “heavenly union” as the twin deities of myths (or the Lord’s androgynous images) there. However, if the Eskimo scene is taken as a starting point, there is another reading to present itself: following the consummation of the “holy” union in winter solstice Capricorn, the first parents are reborn, in the physical sense, in opposing summer solstice Cancer. As is commonly known, starting a family and sacrifice for the offspring are due in this medium (see the well-known image type of pelicans feeding their nestlings with their own blood, which represents the characteristics of Cancer). To this see Susánna’s monologue in the drama by Weöres Sándor (1913–1989) titled Kétfejű fenevad (The Double-Headed Beast): “With Ambrus we have lived in the snow, in the tussocks, in the coffin of a ravaged cemetery and rarely in some remaining hut. If I was already dying of hunger, Ambrus gave me a pot of his blood. Or when he couldn’t go on, I gave him blood to drink. (…) And you know, if you find yourself in mortal misery, what else could you do than make children.” Cf. Weöres Sándor Színjátékok (Stage Plays). Magvető, Budapest, 1983, p. 466

[6] Scene 5, Athens, may be considered as some exception with Eve having the last word, proving that even political canvassing may be authentic of a woman in Madách’s view.

[7] Apuleius Az Aranyszamár (The Golden Ass). Európa, Budapest, 1993

[8] Symposium by Plato, translated by Benjamin Jowett, http://classics.mit.edu/Plato/symposium.html

(02 May 2023)