Miklós Hubay: The Crystal System of the Drama

The Cathedral Which Constructs Itself[1]

If I manage to stay on my own in the “lion’s cave” of the castle[2] in Sztregova, I always attempt the impossible: I am trying to imagine, to fathom, to experience how, for thirteen months, Imre Madách was receiving the impulses to write his work. Always onwards, always upwards, always remaining in the magnetic field of the composition – without going astray, without any adventitious shoots. Thirteen months in the overwhelming flow of motives and thoughts.

The first three scenes were supported by the Bible. Then the eight scenes of Adam’s dream from Egypt to London were supported by history. But the subsequent three scenes – Phalanstery, Outer Space and the World of Ice – were not assisted by any experiences or news. And now, over 150 years after the birth of The Tragedy, we can see that almost each line of these three visions of the future, depicted without any information at the time, has struck home and been fulfilled.

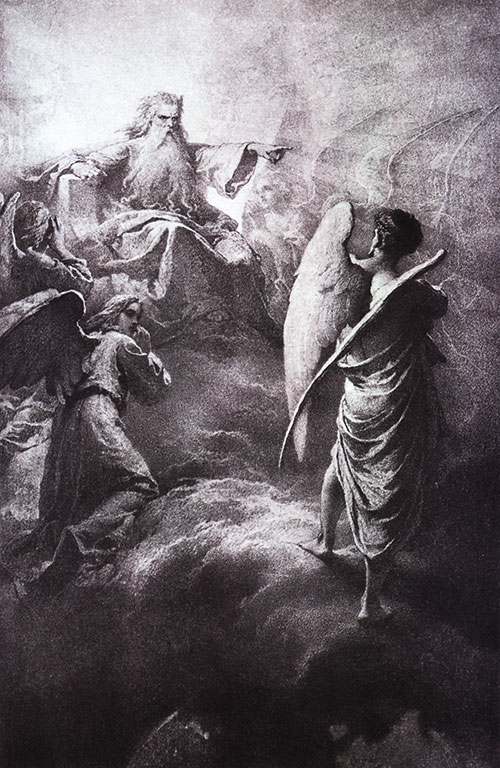

Illustration, Scene 1 (In the Beginning), paper, carbon, 790×503 mm, 1885 (source: mng.hu)

I cannot find any other explanation for this miracle than that the architecture of the drama – once we have discovered its crystallization formula – will autonomously find its way and the cathedral will build itself without the need to copy or mirror so-called reality.

The inner logic of the drama leads to Truth more securely than experience or any other contribution.

One Time Is the Master of Another

The Tragedy in the historical scenes involves Adam’s growing to maturity as well as ageing. By the clock of world history: it is a slow process. Because the journey from Egypt to the Eskimos’ world of ice is long. By the dream-clock this process was magically fast. Adam had his hair turn white all at once in his sleep, like God in Vörösmarty’s poem.[3]

On waking, Adam will be young again. This effect carries one of the most concealed meanings in Madách’s work. What could Madách have meant to say by drawing the individual’s biological path of life as a parallel line to accompany the fate of mankind? I think Madách wanted to make a new and suggestive argument for the necessity of the evolution and destruction of humanity. According to Madách’s concept, life on earth is inevitably finite and the same laws of biology apply to mankind as well as the individual. Both are doomed to life – and to the very same life. (Let us not forget the Madách theorem: “All living things have equal share of life, the same chance of achieving their potential: the age-old tree, the fly which lives a day”)[4] Here, in the relativity of time which Madách has produced in the closed system of The Tragedy, Adam and mankind have equal share of life. The path of life Adam has run in his dream emphasizes and symbolizes humanity’s equally determined path of life.

paper, carbon, 1000×700 mm, 1887 (source: mng.hu)

It is a poetic and impressive symbol of mankind also having one life only. It is a good symbol. And necessary to Madách’s concept. For no matter what energy deficiency or catastrophe will finish the human race off, the last remaining individuals will still be living their own lives and not mourning the extinction of their race. The calf of the last but one bison is not necessarily world-weary.

However, the transfigurations of Adam in the course of the scenes show, like an accurate clock, the expiry of that other living entity, mankind. The Eskimo scene – the last minutes. And yet: later, on awakening, the stopwatch hand will go back to zero. Madách has “Adam, as a young man again” in the instructions to Scene 15.

There seems to be no obstacle for either Adam or humanity to get ready for a fresh start. This is another message of Adam’s rejuvenation: Go! Let us give it a try!

Drama: The Wholeness of Time (1)

If I put Madách’s The Tragedy into the hands of a foreign reader, I advise them to read its very end first, and continue with the beginning only after that, because knowing what is at stake will not throw cold water on their interest, but will increase their excitement rising from the relevance of the drama.

The alternative of to be or not to be in the end, which – and that is where I admire Madách’s genius most – may in the case of Adam mean the suicide all at once of the protagonist and – in him as a forefather – of the entire human race, this alternative is already present in the previous fourteen scenes of the drama as preparation. The thrill of this most relevant alternative is feeding the fire of each line in The Tragedy.

The gestation of the drama through time does not contradict our consideration of it as a single extended moment. (It is no accident that we keep talking about dramatic moments in which we feel a concentrated presence of events.)

The Bergsonian categories of time and duration are simultaneously (and much more emphatically than in life) relevant in the dramatic experience. Within the running time of two to three hours, every little word and gesture has a fully lucid presence. Each remaining word and gesture is ready, with its possibility foreshadowed, to be unfolded. That is why the final moment of the drama gives the experience which we can describe, in the words of Attila József, as “time’s tally is wound up”[5].

In every case, it may be advisable to conduct drama analysis at the light of the closing minutes of the play, and it seems particularly appropriate for Madách’s work. The mythic beginning (with events familiar from the Bible), followed by the great scenes of world history, can easily give the reader – and the viewer in the usual Hungarian stage interpretations – the feeling that what they read and see is but the epic of evolution, some series of illustrations to what they know from the Bible and world history anyway. (Oh, the unbearable historical revues in which stage directors had Adam’s repeated tragedies go down the pan. The flesh and blood Athenian citizens and old heretics about whom the stage directors do not even realize that they are nightmares and that they follow each other with the compulsion of recurrent dreams.)

Of course, the directors of cumbersome dream tableaux may well argue that everything up to the London scene corresponds to known history and that the three scenes after the London one correspond to what we, people who have lived to see the end of the 20th century, are experiencing in our basic anxieties. That the dream scenes are two feet on the ground, among their period sets. And that – apart from the occasional witty commentaries – there is nothing new in Madách’s dream scenes.

But there is! There is a single one thing brought in. And that is what matters. And it is not just some new point of view: it is an Archimedean point. This is where Madách could lift the Earth off its four corners even. Its four corners: myth and the world’s story. It is a moment of to be or not to be.

The moment Adam could have committed suicide… And he did not.

The Wholeness of Time (2)

“Hosanna in the highest! Praise Him on earth and in the firmament!” – this is the opening Gloria, and, just like any personality cult deification (even if it is deifying God), it is too beautiful to be free of conflict. Indeed, Lucifer’s dissonant voice will soon be heard.

When I am putting The Tragedy on stage – because that is what I am doing when interpreting it to my Italian students in Florence and Rome, and now to you as well, oh, gentle Hungarian reader[6] – I immediately cite, into the unison of the Angels’ choir, Adam’s gross screech from the end of The Tragedy: “One jump, as if it were the final act, / and I can say: the comedy has ended!”

It is via this association only that the devotional opening Gloria will gain full meaning: “[I’m tired of] … that puerile band / of heavenly choristers with children’s voices, / the host which never doubts, always rejoices.”

The Wholeness of Time (3)

The boundaries between the concepts of past, present and future are blurred in Madách. The first man lives to see the end of the world – the end of a meaningless world – in advance, and although he might as well commit suicide at the dawn of creation: he does not kill himself. Come hell or high water. Drama in Madách is in the simultaneity of past, present and future. Almost every major drama is in pursuit of the relativity of time, and in its exceptional moments it does achieve that. These moments are usually indicated by the stunned silence of the audience.

paper, carbon, 790×503 mm, 1887 (source: mng.hu)

Masterly Concentration

“Hail, Supreme Goodness!” – says Archangel Raphael and prostrates himself. The order of creation is flawless, worship is flowing towards the throne of God, the music of the spheres can be heard. There is no sign of dissonance.

A short pause. Then the conflict explodes and, 78 lines later, Lucifer announces the overthrow of this Order and a world catastrophe – the catastrophe of this freshly created world. A mere 78 lines – with more than half of them being Lucifer’s two declamations, sheer philosophy, on the properties of matter, on nonsense humankind, on the dilemma of free will, on the determination of Creation itself by the Nothing to name but a few. These two declamations embrace 43 lines. So there remain 35 lines for the plot proper. These 35 lines are full of concise sentences which have become proverbial since. To Lucifer’s first declamation, casting doubt on the sense and success of Creation, the Lord’s response is now classic.

“To pay homage is your part, not to judge me.”

The return, like a hard ball bouncing off Lucifer, is no less laconic:

“That would be out of keeping with my nature.”

Then the rest:

“Niggardly dole, indeed, a Lordly gesture!”

Continuing thus:

“Still, that terrestial foothold will suffice:

there let Negation stand to see the day

when your creation shall be blown away.”

This succinctness and crystallization of sentences are accompanying phenomena of the prevailing dramatic tension. It is only in the clash of extraordinary forces that such diamond phrases are born. Maybe I need not even say that the very same tense atmosphere is necessary for Lucifer to develop his declamations. In drama you can philosophise only in moments of either-or, expanding the volume of these moments to the maximum. Exuberance and concentration: two intermittent states of matter. One is the test of dramatic tension – let us see how much philosophy it can bear –, the other is the result of dramatic tension – weighty and hard sentences of accelerated flight.

The acceleration and rhythm of crisis processes can also be studied here. 78 lines after the celebration of the perfect creation the Angels’ choir, not to be blamed with excessive pessimism, knows it, too: it is the beginning of the Apocalypse.

The Myth of the Future – The Beginning and the End Woven of One Fabric

Everything taken from the layer of myths in his work is preserved as myth by Madách. He does not even make an attempt to rank it with the historical facts or to place it in the light of reason, where etiological myths – like germs in the sun – would inevitably wilt away, or vegetate only as naive tales for children.

The uncritical, non-ironic seriousness – undisturbed faith? and an unbeliever? – with which Madách presents the myth of creation, the Fall and divine consolation – this last one as his own ingenuity – does not at all fit in with the author of the 19th century. Historians of religion and proto-religion in the 19th century rarely took myth seriously, except its poetic values at best.

Madách knows just as well as the man of today that myth – not turned out of its own symbolism – is the human spirit, having always been toubled by the problem of origin, comforting itself – as the guarantee for the tranquility of a sleeping man disturbed by some external noise is the dream.

Enigma and ambiguity follow from this function of myth. This is what may make the last phrase so enigmatic in The Tragedy: “Man…do your best”, the prod into periodical enthusiasm in the midst of the worries of world history waiting for Adam. More than that could hardly have been collected as provisions for the journey.

It is a brilliant feat of artistry that Madách weaves myth and history of one fabric in his work. Besides myth, dreamlike by its very nature, the non-mythic historical scenes are also dipped into dream. It is a feat to ensure the organic unity of the work. However, it is not just that. Adam, entering history, has not only received a mythical image of his origin but of history as well.

In fact, Madách creates the myth of the future in The Tragedy.

Ideologies So Mortal

The composition of The Tragedy is so densely woven and coherent that stage directors get embarrassed about having to insert an interval. But they certainly cannot keep the audience glued to their seat for three, four or who knows how many hours without an interval. It seems particularly delicate to cut into Adam’s dreams, which form a single sequence from falling asleep to awakening.

Nevertheless, this dream is interrupted by Madách himself via scene changes. Division according to scenes in The Tragedy is a conventional tax which Madách pays dutifully to 19th century dramaturgy. In the dream process there is almost no caesura between the Apostle Peter and the Byzantine Patriarch; they are presenting different facets of the same phenomenon.

Unlike the mechanical division by city locations (such as Athens, Rome, Byzantium, Prague), the more intrinsic division is to be heeded which invokes Athenian democracy at the end of the Egyptian scene and Roman dolce vita at the end of the Athenian one. Consequently, the caesura falls rather in the middle of each dream scene, when the promising light of dawn of the dominant ideology has gone out, and the ideal begins to have its distorted features sticking out. It is at this point that Adam’s avant-garde spirit comes into play, stamping out his previous ideology without hesitation and starting to profess its opposite.

It is almost impossible to insert an interval in the dream process. Not only because of its oniric nature, but also because Madách was not a bit concerned with the defence of particular ideologies (cultures and worldviews). He focused a lot more on the transience, the ephemeral life of these.

“All things that live, though wholesome in their life,

must die in turn: the spirit will depart,

but their remains are left, a foul cadaver,

from which a murderous contagion issues…”

Scene 2 (The Garden of Eden), paper, carbon, 790×503 mm, 1885 (source: mng.hu)

Perhaps the Hungarian people could endure the marxist promise of salvation yoked onto them in Yalta partly because they had been vaccinated against it by Madách well in advance. Then, in ’56, all that had been curbed erupted with elemental force.“We’ve had enough of this!” Everyone could already feel the deadly microbes in the air. Even the main marxists did. What keeps happening to the man of The Tragedy is that he creates an ideology with enthusiasm and commitment but, in the meantime, he is turning crestfallen (presumably because he has unquenchable thirst for absolute truth in his heart) and gives it all up.

Man and Woman

The Tragedy involves “man” [“ember” in the Hungarian language] and this – especially in the Hungarian language – means an adult male human [“férfi” in the Hungarian language]. “Woman” appears in the work as a riddle, a catalyst, an irregular factor, full of paradoxes.

In Apuleius, Isis says that there is only her, and all the other goddesses are simply her local names (Venus in Cyprus, Diana in Crete, Minerva in Athens, Proserpina in Sicily, even the dark Hecate is also her…).

In Madách, Eve is the partner of a slave flogged to death, the proud wife of a Greek military commander, and a cloistered virgin, and a marchioness, and a middle-class girl, and …

Adam is eternal resumption, Eve is eternal transformation.

English translation by Mrs. Durkó, Nóra Varga

Published in Hungarian: Szcenárium, September 2018

[1] Extract from Hubay Miklós: “Aztán mivégre az egész teremtés?” Jegyzetek az Úr és Madách Imre műveinek margójára. (“And as for This Creation – What’s the Purpose?” Notes on the Margin of the Works of the Lord and Imre Madách) Napkút Kiadó, Budapest, 2010

[2] Madách Imre (1823–1864) was born in Alsósztregova (Dolna Strehova) in the historic region of Upper Hungary (today Slovakia) and wrote The Tragedy of Man there in 1859–1860.

[3] See Prologue by Mihály Vörösmarty (Hungarian poet, 1800–1855): “…The earth turned white; / Not hair by hair as happy people do, / It lost its colour all at once, like God,…” translated by Peter Zollman, in: http://www.babelmatrix.org/works/hu/V%C3%B6r%C3%B6smarty_Mih%C3%A1ly/El%C5%91sz%C3%B3/en/2123-Prologue) ]

[4] The quotes from Madách’s work are taken from the English translation and adaptation by Iain Macleod, Imre Madách: The Tragedy of Man, Canongate Press, Edinburgh, 1993 at http://mek.oszk.hu/00900/00917/html/

[5] From By the Danube by Hungarian poet Attila József (1905–1937), transl. by Zsuzsanna Ozsváth and Frederick Turner

[6] Miklós Hubay (1918–2011) was a Kossuth Prize-winning dramatist and translator. His first piece (Without Heroes) was staged by the Antal Németh-headed National Theatre, Budapest, in 1942. He worked as dramaturge at the National Theatre between 1955 and 1957. He was professor at Színház- és Filmművészeti Főiskola (Academy of Drama and Film) from 1949 to 1957 and later between 1987 and 1996. The backdrop to his career was Florence from 1974 to 1988, where he promoted Hungarian literature at the University.

(02 May 2023)