A festival organiser, even if he would love to behave like an anthology editor, cannot really behave like that. This latter one may freely rely on his intuitions while picking the poems when it is hard to define his object. On the contrary, a festival organiser has to fit the complicated and difficult complexity of things into his own “anthology”, during which act his attention is mostly focused on the risk factors of the given historical moment. One of the greatest sadness of the theatre is that it is unable to keep its masterpieces alive; not as if their preservation were practically impossible, but because any theatrical masterpiece may lose its validity owing to the changes that a human being goes though during historical times. Eventually the creators may get cemented in the historical times of their own masterpieces whilst they should reinvent the changeable present from day to day. And this is not always successful. It often happens that the creators of masterpieces make compromises, so they integrate into the undivided present time, which they may lose sight of in the end as a result of doing so.

Perhaps this explains it why at the second MITEM after listening to Luc Perceval’s or Matthias Langhoff’s presentations my initial enthusiasm changed into indecisiveness similarly to those situations when we face heavy commonplaces.

Banality in a theatre builds up in a very complicated way. It appears to be exposing itself with the virtuosity of the actors throughout a long period of time while applying a wide range of the abundance of the means of theatrical techniques etc. The performance itself often turns out to be an overloaded and hyper-technologized structure whose topic – therefore the essence of its legitimacy- is some naivety which is not even touching. Just imagine a factory sprawling over several hectares mass-producing the same kind of handle. The product is in short supply of course, therefore the spare parts -in a grotesque way- seem to have more attention and importance than they should otherwise.

The truth is that the “conscience” of contemporary theatre should be identified with not more but narration and cynicism even if all its respect is taken into consideration. Everybody or almost everybody regards it as important that the same handle should be manufactured and the same story should be told about the collapse of the present and the tragedy of man. However, the same handle sometimes may as well open a refrigerator door: and this is where our deep frozen hope and love lie; it depends on us if we are capable of opening the door; yet opening a refrigerator door does not require a heart, and our heart is stored in the refrigerator anyway…

Attila Vidnyánszky, this artist with tremendous talent invites highly respected artists, who he admires, to his festival at the National Theatre. However, this festival is a hazardous game. Some of the admired artists may again reinvent the present, while others being unable to do so are trying to force the present to compromise.

(Some others are such opportunists that they publicly insult this present, moreover they do it on the same stage as they are invited to, as the actors of the Viennese Burgtheater did. A festival is a hazardous game… g.e.d.[1])

Despite the unpredictable “opportunisms” that obviously characterises the orientation of MITEM, it is intended to be rather the refusal of any compromise on behalf of the “dialogue” with the contemporary theatre regardless of the location of the theatre. Similarly to the character of the National Theatre when Vidnyánszky defines the profile of the festival he strictly excludes performances with the jargon of the crumbling subculture as well as social theatres. The festival refuses petty thinking, the so-called solidarity theatre, hunting for “target audiences” as well as the “generation principle”. Vidnyánszky is not willing to take part in the global culture of flouting and the declaration of the menial character of human nature, therefore in basically nothing that the civil servants of culture usually appreciate in art, on the contrary, he more and more openly voices its class strugglistic character. Whether intended or not, but the main orientation of the MITEM programme is the same as director Attila Vidnyánszky’s main interest is: focusing on the archetypes. And if it is so, then it can positively be said that the festival is oriented to a powerful and creative modernity.

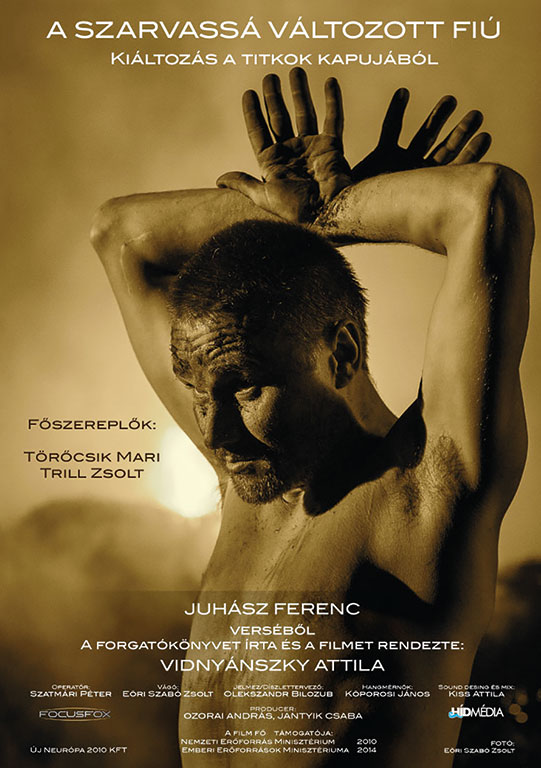

Modernity looks back on the archetype as it sees the future lying in it. In the stage production of Isten ostora (Flagellum Dei) Attila Vidnyánszky shows the birth of Hungarian intellectualism in the highly polarised field of Asian shamanism and doctor Fausto; ethnic groups may as well come and go, play around, mix and mingle with each other and dissolve hatred in erotics. The world of Hungarians juggling with the nostalgic sentiments towards primordial roots and the eagerness for the transformation of nature creates a vivid vision of the birth of European culture in a concentrated way. The film adaptation of A szarvassá változott fiú (The Boy Changed into a Stag) by Attila Vidnyánszky follows through the raving way of the full spectrum of senses during a traditional funeral. In Kutyaház (Dog’s Cage) by the production of the Ukrainian director Vlad Trockij a community forced into war redefines itself by its return to the archetypical quality of songs at the threshold of an apocalyptic havoc of cruelty and cannibalism. The strong yearning for return to the archetype and simultaneously the desire for individual freedom creates such a constant contradiction in modern people, whose dissonance leads to the definition of themselves too. The dramatic state of mind of modern men originates from this dissonance. Owing to this dramatic and exceptionally modern state enables theatres to keep up their dynamic existence-no matter what the expectations are.

I attempt to say that these days MITEM is one of the rare and supposedly last modern cultural events. Attila Vidnyánszky with the festival and its programme is one of the last contemporary modern artists. It is also possible –best of luck to us- that Vidnyánszky is one of the members of such an indispensable minority that is able to define a historic era.

Translated from Romanian original into Hungarian by Edit Kulcsár

Translated from Hungarian into English by Anikó Kocsis

Sebastian-Vlad Popa: j’aime mitem

Sebastian-Vlad Popa (b. 1968), the excellent Romanian aesthete, theatrologist, professor and editor of INFINITEZIMAL, has had close contact with the director Attila Vidnyánszky-led Nemzeti Színház (National Theatre) for two years. He presented a paper at the conference on the grotesque last year (Kings On the Backstairs) and visited both MITEMs. This essay gives account of his experience at the 2015 MITEM. He emphasises that the aspects of selection for the festival suggest an intense and creative modernity which sees the future in turning towards the archetype. As telling examples of this, he appraises two directions by Attila Vidnyánszky, one being the stage production Isten ostora (Flagellum Dei) and the other one the film Szarvassá változott fiú (The Boy Changed into a Stag), as well as the production Dog’s Cage, directed by the Ukrainian Vlad Troitskyi. Finally, he voices his opinion that MITEM “is one of the rare and presumably the last modern cultural events”.

[1] Quod erat demonstrandum – which is what had to be proven.

(15 April 2016)